Meteorwrongs (2018-ongoing)

If it’s not a meteorite, it’s a meteorwrong. Ongoing series of drawings, collages, installations and texts.

Investigating the life of things across space and time

Text and audio work; 6.46 minutes

Written for The Surround Christmas Album 2016

by Sarah Gillett

Uganda is hot and dark. Late into the December night we sit on planks in the back of a stripped out land rover. We are driven faster than our bodies would like, the speed rattling my bones, teeth, brain, recording equipment.

On one judderingly heavy bounce I hit my ankle on the edge of a sharp metal hole, its bolt long gone, along with the seats. The crew are grumpy but our presenter looks carelessly cool despite the journey. I stick my face out of the window but it’s like a hairdryer blowing into my mouth. I pull my head in. Huge wet insects swarm in the headlamps. When we stop, the windshield and wipers are smeared with twitching legs, torn wings and oily leaking bodies.

The Buhoma campsite is well-established, with portable loos and cabins for tourists. I hand over our permits and write down facts for tomorrow’s script. At a longitude of 29.7 degrees and latitude of 1.05 degrees the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is old, complex and biologically rich. For generations the Batwa people fished, harvested wild yams and honey, and buried their ancestors here until access was closed in 1991 when the forest was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site. The forest occupies 331 km² and is home to many endemic and critically endangered species, including 340 mountain gorillas, almost half of the world population. Companies offer tours tracking the gorillas but what we are looking for has meant many months of darknet research and negotiation with local guides, as well as substantial investment from our client. Bwindi means darkness.

We tie rubber straps around the bottom of our trouser legs to stop leeches and film the presenter clambering up a steep hillside, kneedeep in mist. A team of Batwa men hack their way through tangled undergrowth with machetes. They carry food and water for us. Also machine guns. The bamboo rustles. We make scheduled stops and record the presenter talking ernestly to camera about the primeval forest, its importance as a site, its smell and sounds.

In the blue hour, the darkness of the forest has a feathery touch. Our guides tell us that the mountain gorillas build their nests in small evergreen understory trees known locally as Echizogwa. The air is alive with sound, amplified in the dark. We hear the tiny snap, crackle and pop of insects. Chimpanzees and vervets move high in the canopy and the hollow ha ha ha call of a civet echoes through the trees. Underneath it all is a thrumming, ringing vibration. The Batwa move in slow motion, lean and low to the ground. Behind a knot of dense Achanthus bush we set up the infrared cameras and mic the presenter. Slowly we push the optical lens through the leaves and watch the monitors.

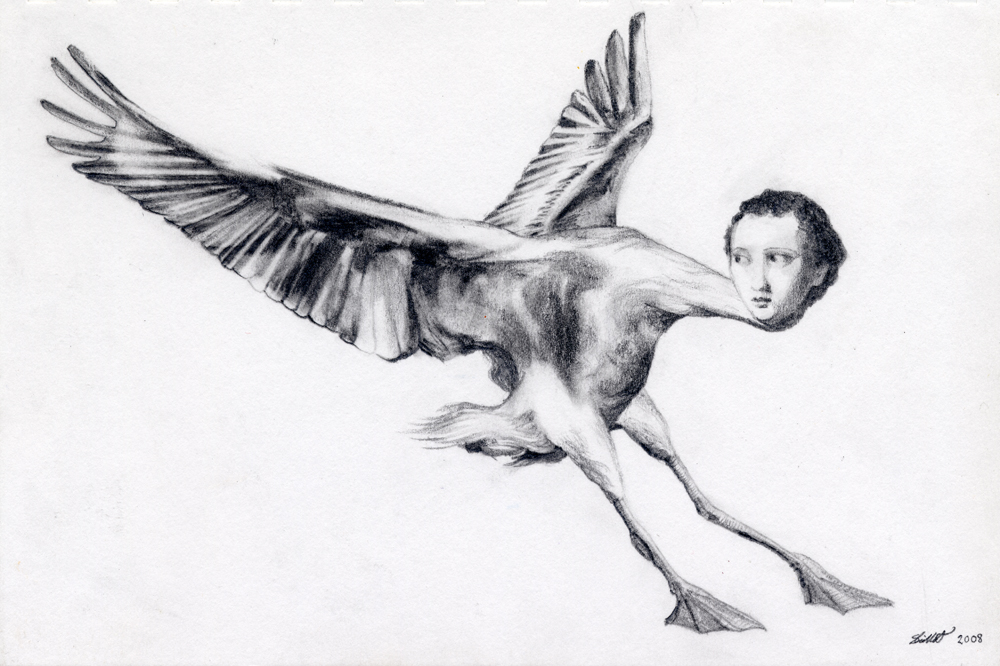

The angels are gathered in astronomical numbers. Eyes shut, heads down, their wings thud the air as they stalk from tree to tree, 30 feet above us. Seven sentinels, the Archangels, stand silently in a suspended circle like stone ghosts. Lower, vast flocks of angels drift slowly past, mouths open in voiceless song. The sleepwalkers’ hands are in constant motion, fingers twitching on the end of long hairless arms that bend in the wrong direction. I look away from the monitors and my stomach lurches. I see nothing in front of me. I see only the dark.

The presenter is whispering about history and physical strength. ‘Once the most powerful creature on earth, the angel was thought to be completely extinct until earlier this year when cranes were built to explore the abundance of wildlife here. No one suspected how many there were, living in the canopy, but there are thousands and thousands here. Anthropologists reason that the angels survived here because of the forest’s high elevation and equatorial location. During the Pleistocene era, it was a refuge from the glacial floes, protecting many species from extinction and encouraging the evolution of others in its microclimate. From this paradise the first modern and early humans ventured out around 70,000 years ago.’

The cameras focus on tiny Cherubim with huge ears racing across the clearing, flitting over the ground after mice and beetles. ‘The smallest of angels may only be a foot long’, says the presenter, ‘but they are energetic and determined killers.’ He stretches out a hand to touch the flight feathers of a slow moving beautiful adult Virtue.

On the monitors, thousands of heads snap towards us. Millions of eyes open wide.

If it’s not a meteorite, it’s a meteorwrong. Ongoing series of drawings, collages, installations and texts.

For Nin, poor Nin. For Nin neither.

So much for you to hear and fear, that owl hoot and dog bark is not for you. Come out from under your wing soft down. You are needed.

Most people whose mental digestion of the marvellous is quite robust will refuse to believe this account, and yet there must be a few whose hair has been stirred and whose hearts have beat an unusual tattoo at the sound of a ‘Something Inexplicable’ in the watches of the night. Our conclusion is that there are such things as spirits, and in believing, we tremble…

Sarah Gillett is an artist and writer from Lancashire, UK.

She currently lives in London.