Mantle (2016)

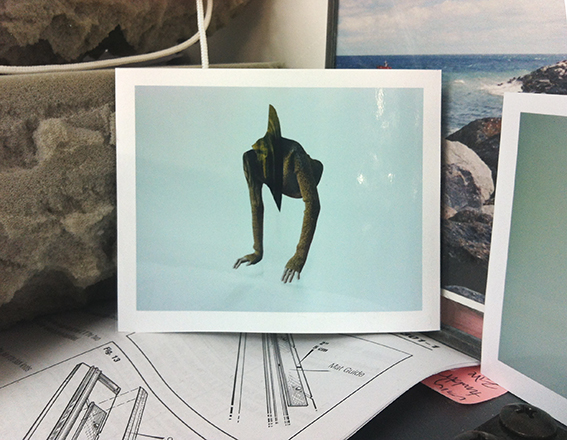

As if standing in front of a green screen this mysterious figure invites us to imagine a space in which anything is possible.

Investigating the life of things across space and time

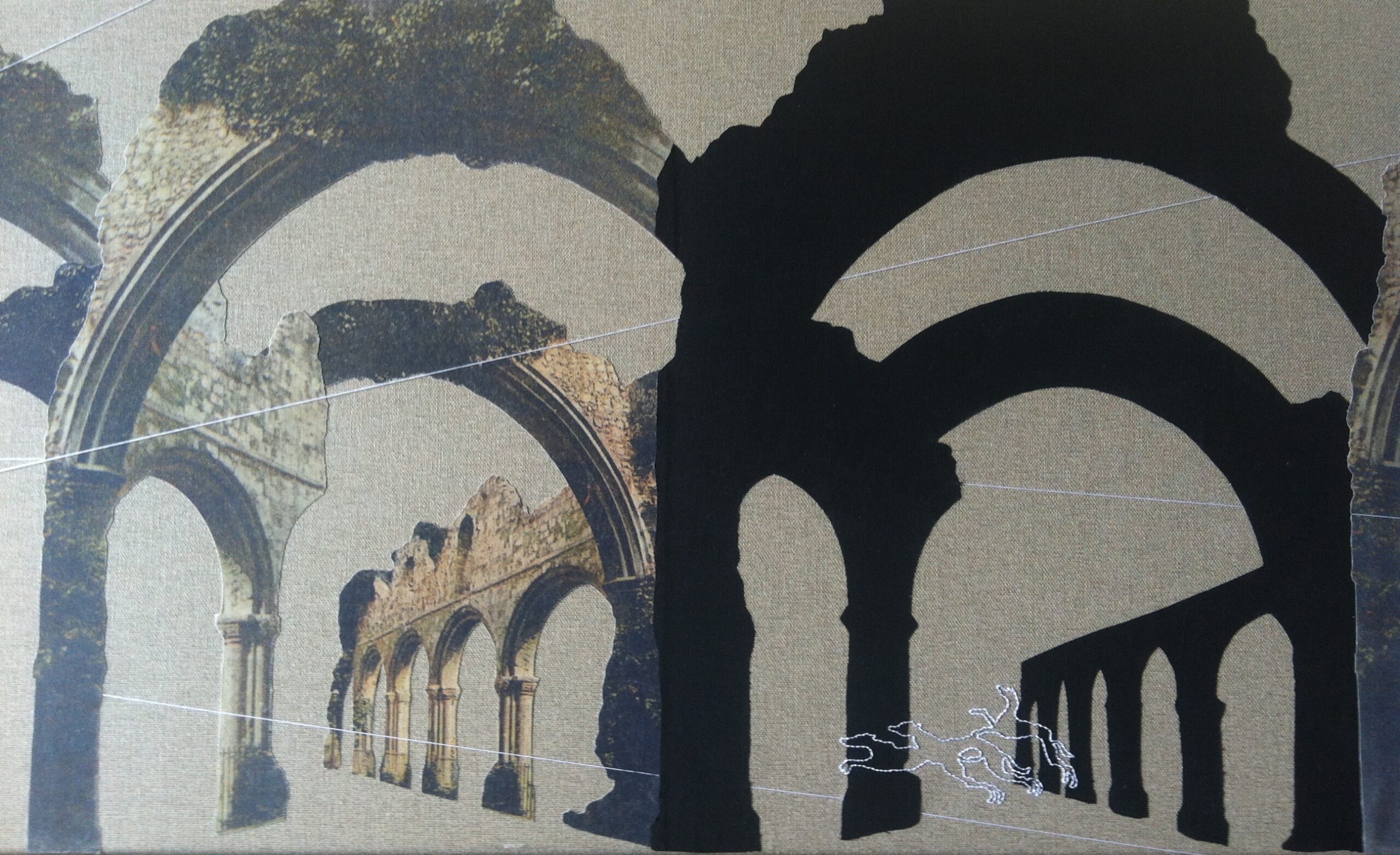

Gallery of Cleave details and exhibition installation

Paolo di Dono, called Uccello (1397–1475):

The Hunt in the Forest (c.1465-1470)

tempera and oil, with traces of gold, on panel; 177cm x 73.3cm

The Hunt in the Forest is held in the collections of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Uccello uses a Renaissance colour palette with red and green colour pigments and accents of gold, now faded to give the painting a magical jewel-like quality. This is reinforced by the overall unreality of the scene and Uccello’s affinity for Gothic art, as evidenced by his creation of stylised patterns. In Cleave, a gold thread runs through the textile collage pieces.

The word cleave is interesting for its opposite double meanings:

I also took inspiration from Uccello’s preparation techniques to stretch cotton over board before gessoing and sanding down repeatedly to create a matt, smooth surface.

Cleave was first shown in Quarry at the Brocket Gallery, London in 2016.

As if standing in front of a green screen this mysterious figure invites us to imagine a space in which anything is possible.

Like Paolo Uccello’s Hunt in the Forest (1470), Quarry came into existence from dark to light. Uccello’s technique created a theatrical depth and drama that I wanted to capture.

In this exhibition Paolo Uccello’s painting The Hunt in the Forest (1470) is the basis for a series of works combining printmaking, needlepoint, text and collage

In Paolo Uccello’s preparation of his wood panels for Hunt in the Forest (1470), he glued canvas over knots and scored lines into a black underlayer of paint to mark tree branches and vanishing points.

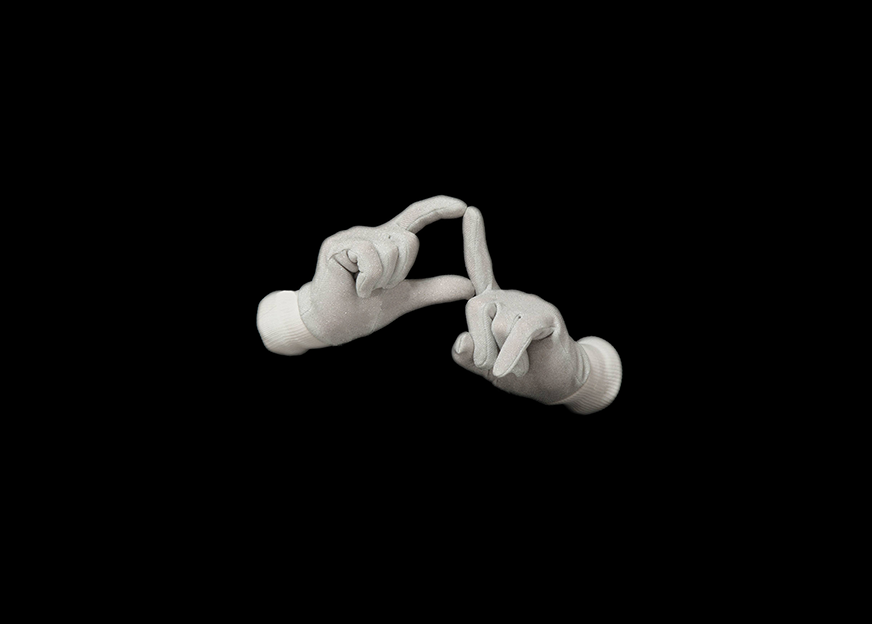

Salt is mined, extracted and evaporated. Stitching mends holes, fills in blank space. This artwork began life as the back of an unfinished needlepoint and grew into an exploration of geology and archeology.

This work started as an old needlepoint completed by an unknown sewer, that I unpicked, leaving only these trees intact. It was a way for me to look at the stage without the players.

Falling is an uncontrollable action. When we fall (over, apart, in love, asleep) we become vulnerable; quarry. Caught between spaces this figure falls headfirst and downwards.

I wanted to create a work that used just a few very strong elements to show the power of a repeated shape. I drew this grid over Uccello’s painting to reveal his mastery of perspective and as the starting point for Trace.

The relics and ghosts of long ago are brought together here as if in a wild dream of nature. Starting from the verticals of Uccello’s trees and dotted lines he cut into the wood I wanted to present a landscape of fragments that offers a framework for a narrative.

This conversation between Sarah Gillett and the writer Amy Lay-Pettifer digs deeper into the artist’s relationship with Paolo Uccello’s painting The Hunt in the Forest (1470) and her wider art practice.

The dogs in south London are running. One of the big ones slows down as it passes me and I step back as its nose swerves into my crotch, waving my arms as though that would make any difference. If it were really hungry it would just eat me but I get a face full of hot meaty air and it’s a lucky day.

The story of a spontaneous polaroid film collaboration with the artist Luke Harby

Joseph reaches down and picks up a shell. He hands it to the boy, who is dragging a red plastic bucket across the sand. “Here. What about this one?”

Bill assesses the offering intently. “No Daddy,” he says firmly, “It’s broken here, see.”

It is late when I see you moving into the flat above the pub opposite. Must be past 11, because I hear the doors swinging open, hot blue noise gulping for air.

Sarah Gillett is an artist and writer from Lancashire, UK.

She currently lives in London.