There was something wrong with the sea. The waves were oily and green and forest-filled, like the kelp had been ripped from its leathery footholds by a far away storm and carried here by the currents. A thick tangle of tentacles and skeins spread across the water holding bulging sacs that popped open as they reached the surface and spewed hundreds of bugs onto the undulating skin.

Zoom in and focus.

The bugs bred two by two and then in threes, fours and fives. Each time a new bug emerged from its carapace it was black and squashy as a sour cherry, its antennae stalk stiff and shocked, twitching in unison with the thousands of others multiplying, crawling over each other, breaking through heads and shells, trailing gooey legs behind them.

Above, gannets squealed and dived into boat windows. Our men, their thick hands pressed to cauliflower ears, jumped overboard feet first and sank without a struggle. Then the rippling black curtain rose from the sea and the bugs began to mimic the cry of the gulls in a huge crescendo of metallic voice that hurt our flesh, bellies and teeth.

Just as our ancestors had abandoned this place before we had no choice but to go, leaving doors and gates swinging as dogs and cats leapt away in front of us and the slick reached for our ankles behind. In our backyards the chickens flurried the ground and the pigs bulldozed fences down. In the fields the goats worried under the one remaining star, the night thin and dark.

In the blackness the mutation grew faster. It sealed off the village street by street, covering the steep cliffs, the houses, the shops, with globs of spiralling darkness, a milky way on land, a galaxy of atoms newly formed with insatiable agency. Footballs, pot plants, tins in kitchen cupboards, TVs, photograph albums, all wrapped tight and swallowed. Almost tenderly, its fingers brushed the dust from picture frames and ornaments, reaching up to stroke the cold smiling faces. Touching the mouths and learning the shape.

Not all of us managed to get out. Old Marigold was sitting in her armchair having her afternoon pot of tea and two custard creams. Mr Jamieson was in his shed, listening to the radio and re-living the old times in his head. Tourists whose names we didn’t know but nodded to outside the post office were on the beach or making love in the bedrooms of their holiday homes. Pets in boxes under the stairs, in cages in our children’s bedrooms. We looked away but we heard the sounds.

We heard the sounds.

Long and cruel hauntings. Disappointed shouts from the shoreline. The hounds and barks of rabbits, all the tumultuous cymbals of birdlife and song, in one great gasp of audio. Our ears we wrapped with blankets to block out the noise. Our eyes were blind and could not see. It was upon us.

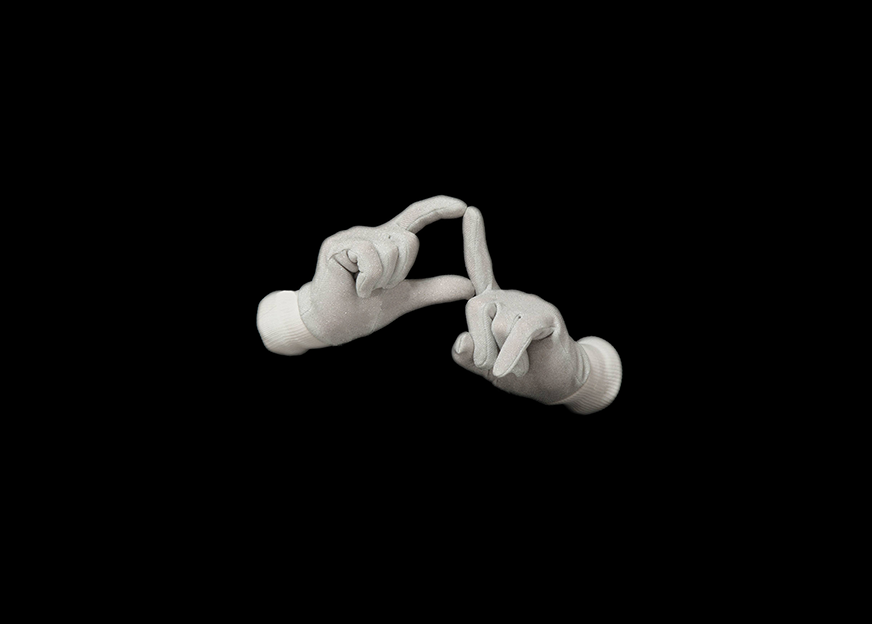

Now we ran, falling over our feet, stumbling to our knees, losing our shoes. Our belongings we dropped as we ran, tumbling down scattering scree, clinging to the short stumps of dead trees as the mountain drew dark lines in the rocks, gaps wider than our blank open eyes. The ground split and shook us apart. We joined the rattling landslides of soil and roots, reaching for each other, grabbing for belt loops, hair and buttons. Any human clasp to crook our fingers into.

The beacon flickered sideways, its light hot and yellow on our faces. The flame tugged away from its fuel, dying sparks flying into the night. We climbed the last hillside with shadows burning in our eyes. We crawled over soft, dark things and felt the crunch of bones under our knees, jelly wetness between our fingers. We were the bugs, trailing our gooey legs behind us. Collapsing in the wavering circle of light together.