It is late when I see you moving into the flat above the pub opposite. Must be past 11, because I hear the doors swinging open, hot blue noise gulping for air. The metal shutters churning and clicking into place, shouting pissheads smoking cigarettes, hunched into their shoulders, into their oily polyester coats. October, nearly November.

“Night, Alan.”

“See you at the match -”

“Taxi!”

“Need some fags from the offy first,”

“Night is young, lads!”

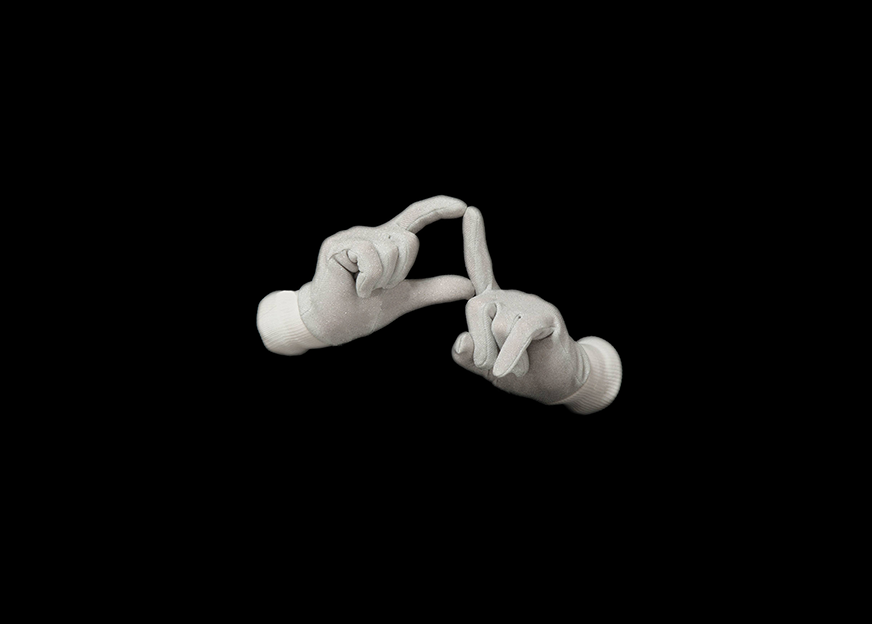

I don’t mean to watch but I can’t keep still and I need something to concentrate on other than numbers. The TV shouts light at me but my brain is wired, growing pains in my legs. I try to read but the words are small fly-deaths on the paper, flat squiggle shapes printed in a uniformly random pattern. I turn the book upside down but it doesn’t make any difference. I have lost the ability to decipher any human code. I am drained by counting and am still full of nothing. So I watch as you carry up cardboard boxes, eight of them, into the room darkness, a parallelogram of orange urban night on the floor where a rug should be. A monochrome man, white skin, grey t-shirt, jeans probably, I can’t tell.

You bend down and fiddle with something in your hand, then lamplight – steel head, ribbed arm, flexed. The light shining up and out at an angle. You raise a bottle of beer and lean back, back, pouring it into your mouth without touching the bottle. I see a tattoo of a flock of birds on your left arm. I make up conversations. Hi there, I’m Penny, I live opposite you. I love your tattoo by the way -. Then what? Awkward silence as he takes in what I say. I blush. He opens his mouth and I back away, sorry, sorry, I just realized I’m late for something. Need to get back to wasting time, counting threads. Days and days killing time, waiting until it is all dead. Hundreds and millions of years.

I eat up your activity, gorge on it as I sit and work, listening to the dried up voices on the radio. I don’t need to look at what I’m doing, I’ve been doing it so long that it’s like touch-typing, my fingers know the way.

You paint the walls, standing on a set of wooden steps. You’re not particularly good at it, but at least you are doing something. You don’t have any furniture. Maybe I should offer you one of my chairs but then I would have to find something else to hold the shelves up. The chairs are stacked in such a way that I can climb them and reach through between the legs to wriggle the books out. Above I have wedged in a chest of drawers, horizontal brooms and mops to hang my clothes from. A pile of mirrors on the floor is an expanding pool of framed reflection that I look down into from my makeshift bunk-bed. I know this is not normal. I hoard things.

A man comes to read the electricity meter.

“It’s just in here,” I say.

“This is quite some storage place you’ve got here,” he says.

“Mmm,” I say.

“You in the furniture trade then?” How does she ever get any of it out? It’s like a jungle.

“Sort of,” I say. “Family business, long story.” That’s my standard line. Smile.

There must have been a bed in there already because I watch you appear in the mornings from below the level of the windowsill, and disappear again at night, like the sun. I watch you slurp coffee from mugs and only wash up when you run out of anything to drink from. Shall I pop over now, offer him a cup to say hi and welcome, or wave, knock on my window to catch his attention, smiling with freshly-washed hair and enthusiasm? No. I am trapped inside my shell, inside the loneliness that claws at my guts and spills out to all the corners of the flat, coating everything in its sticky cobwebs. I just watch, silent under the moon.

When I have to go out I tentatively cross the road, struggling to pull my jacket around me. To stay calm I read signs on shops, walls, buses: Lordship Road; Doorway to Value; Things on Sale. If I have to ask for anything I go red in the face. The embarrassment. My shame. I worry that I might bump into you outside, that I will die if that happens, the waking, shaking of death, my heart drumming me onto war, into the fight. Back inside, I run to the window, to the hole in the curtains, to watch you, invincible and lazy in your routine. I work all day and night, waiting to see if it will happen, happy event. Years.

The dense hedge of trees is green now and a girl in a jade green coat walks past. The flat opposite is bare. The blank windows give nothing away. The lamp is there on the floor but you are not. The mattress is pushed upright against the window, things stacked by the wall. Gone, all gone again.

I am still counting.