Radar Beach

Joseph reaches down and picks up a shell. He hands it to the boy, who is dragging a red plastic bucket across the sand. “Here. What about this one?”

Bill assesses the offering intently. “No Daddy,” he says firmly, “It’s broken here, see.” He holds out the shell for Joseph to see. Along one edge, there is a tiny nick, and when Joseph looks at the shell against the light, he sees a crack running straight across, all the way through from one side to the other. The boy smiles at him. “It’s ok Daddy,” he says. “It’s quite difficult to find really good ones. If you want to keep it, put it in your bag.”

Joseph is carrying a small blue rucksack over his shoulder. “Can’t keep them all Bill,” he says, and throws the shell far, far out to sea, where it plops into the yellow water without even a splash.

The boy has already moved on, is crouching on the strip of sand on the tideline, poking a sprawling tangle of weed and plastic with a stick. Flies artfully avoid each other as he wafts the air. “Poooo, stinky,” he says happily, trying to catch Joseph’s attention by flinging lumps of crispy weed at a curious dog drooling over a faded orange polystyrene carton, still greasy with burger fat.

Joseph is standing looking along the beach to a cluster of striped windbreakers, flapping parasols, and women in sunglasses spraying sun-cream on each other and shrieking. The wind funnels their voices into snaking waves like the hard ripples of sand underfoot. He starts to walk towards the brightly-coloured shapes.

Bill drops his bucket and runs ahead, shouting, arms stretched out wide as wings. “Daddy, Daddy, look at this one! Look at this one!”

In his hand the boy clutches an oyster shell, barnacled and mossy, its inside curve a pale violet iridescence. His hair is thick and dark like Joseph’s, damp curls glued to his eyelashes and ears. He whoops with joy, his little heart beating fast as anything, his bantam stance triumphant.

They stand together, the father, his son and their two elongated shadows, silhouetted in the bright sparkling light. Joseph’s heart skips as he looks through Bill, his curls perfectly framing one of the beach women as she sits reading a book. “Perfect,” he says. “Let’s have an ice-cream to celebrate. Go get your bucket.”

He has already started to stride away so by the time Bill grabs his bucket, Joseph is half-way down the beach. The bucket is too heavy to lift so Bill tips it upside down on the sand and shakes out the shells. “Daddy!” But his voice is a seagull’s cry on the wind and Joseph treads steadily on. Bill sits down.

I can look at them now and then when Daddy comes back with the ice-cream he can carry for me. Here is a white one with a hole for looking through. I can see you Daddy! And this one has scribbles all over it and this one is pink and shiny like a jellybean but it is just a bit salty not sweet after all and it is prettier wet so I can pour water over all of them and see them properly I will dig a hole and put them in it and pour water in or make a way to the sea so the water keeps them wet all the time. Here is a big rock I can’t move it but if I dig around it and make a moat and use these flat stones around the outside to make a wall then the shells will be safe and the wind won’t blow them away.

“Hello Bill,” a voice says, and the boy stops his chatter.

“Oh hello Mark.”

“It’s a 99 with extra strawberry sauce,” Mark says, “but it melted a bit on the way over, sorry.” He passes it over and Bill sucks the drips from round the wafer edge, licking up all the strawberry juice in one swivel.

“Wow,” says Mark. “I can see you’re an expert at that.”

The boy shrugs. “Where’s Daddy?”

“He just saw some friends he wanted to say hello to,” says Mark, and sits down, folding himself up like a deckchair and blocking Bill’s view of the group at the far end.

“Need some help?” Joseph calls to two women struggling to anchor a windbreaker.

“We don’t want to put you out,” says one.

“Yes please,” says the other, grinning. “I’m Sophie. This is Helen.”

“Joseph,” he says, holding out his hand.

A third woman is already sitting on her towel, facing the sea. She doesn’t look up from her book.

He takes a big, heavy stone in two hands and brings it down with a thump on top of the first pole. Thwack. Should do it. Sophie and Helen watch him as he makes his way round their camp, make admiring noises to encourage him on. Thump. Thwack. Thump. Thwack. Struck gold here Joe.

“So what do you do then Joseph?”

“Well Helen, I’m an architect.” Always gets the ladies interested, that one.

“You must have a nice house then,” she says.

“I mostly work in the public housing sector,” he says. “So a lot of my days are spent behind a desk, working with councils on local planning laws, working out height limitations, parking requirements, window regulations, that kind of thing.” Humble, honest Joe.

“And how do you spend your nights?”

The reading woman looks up. “Sophie!” she says.

Joseph hears the crunch of feet approaching and turns to see Mark. “I waved,” he says, “But you didn’t see me. Where’s Bill?”

“Hi,” says Helen. “I’m Helen. Do you have another friend too? The three of you are welcome to join us if you like. We have wine and they sell beer at the shop. Nice tattoo by the way.” A flock of birds in flight.

“Hi, I’m Mark – thank you. No, erm, Bill is – ”

Joseph shoves a £5 note into Mark’s hand, glaring. Is he deliberately trying to ruin my day? “Bill’s been waiting for you to get here. I was on my way to get ice-creams and beer, in, you know, a throw-back to being kids again but he’s been going on about wanting to catch up properly with you, so…”

“Sure,” says Mark. He can just make out Bill, a solitary little figure huddled by the water. “I’d better get over there then.” He nods, uncertainly, to the standing women and holds his hand out to the woman reading her book. Ulysses. “Nice to meet you,” he says.

“We didn’t really,” she says. “I’m Alison.”

Mark shows Bill the glacial beds cutting into the cliffs. The beach is scaffy here, thick with twigs and tattered feathers, tin cans and dried dog shit. The boy looks disconsolate.

“You can see the layer, here, where the ice was,” he says.

Bill nods, swishes his stick around. “Where’s Daddy?”

“Let’s see what we can find to add to the fort, eh?” Mark says, searching for Joseph in the camp. Yes, he’s still there, lying on his side, talking to Alison. Poor kid, all he wanted to do was play with his Dad, and instead he got me. Again. “You know, Bill, this place is very special.”

“No it isn’t,” says Bill. “It’s just stupid and smelly.” He kicks the half carcass of a dead crow experimentally and it desiccates to dust, a puff of motes hanging in the golden afternoon light.

“Look at the rocks,” says Mark. He pulls the tired, resistant boy to him.

“Oh wow,” says Bill.

They are everywhere. Lines of shells, stacked one on top of the other like tiny bowls, balanced in time. In between Bill sees discs and tiny sticks and sometimes triangles, glinting.

“These are fossils of fish vertebrae,” says Mark, “And these are seeds, and this is petrified wood. If wood gets buried in mud, like here, and stays covered, then over millions of years, the wood turns to stone.”

The boy runs his hand across the rough surface of the rocks. “How can we get them out?” he says.

“We don’t need to,” he says. “Nature does it for us. Let’s see what we can find.”

On their hands and knees, Mark and Bill shuffle in the scree, turning over stones, breaking apart sandy clumps of soil, consulting each other on the significance of this shell stack over that plant impression.

“What’s this?” says Bill, holding up an inch of smooth arrow-headed weight.

“It’s a shark’s tooth,” says Mark.

Bill holds it in his palm, amazed. The tooth is warm and stained like Mummy’s tea when she forgets to take the teabag out before the milk goes in and it bobs along until she squeezes it against the side of the mug and brown clouds scurry around the edge. He bites it cautiously. It is hard as his own teeth, harder probably. There is a brown woody bit at the bottom with lots of holes. “The root,” says Mark.

It is a magic thing, he is quite certain. ”Can I keep it?” he asks.

“Of course, it’s yours. Finder’s keepers!”

“Finder’s keepers! Finder’s keepers!” the boy runs off back down to the sea, whooping and flying, arms outstretched wide as a bird, a dinosaur flapping in the wind, tooth in hand, looking up at the blue, blue sky, and there is his Daddy, and he waves, and his heart is full of joy for Daddy and the shells and the fort and his friend Mark and especially for the shark’s tooth, which he found and which will always be his and by the time Joseph picks him up he is sobbing and he is kissed and hugged and comforted all the way home, the tooth pressed so tight in his little hand that next morning it has left an impression in his flesh and when he feels in his mouth for his own wiggly tooth he remembers that Mummy says there is another tooth underneath and he decides he will be a shark hunter when he grows up and he will be famous for collecting the most shark’s teeth in the world and he will line them all up on the floor and look at them everyday.

And he puts the shark’s tooth in his secret tin with his best shells and his Moshi monster and his elastic bands and the lollipop that Sam gave him and the postcard of the stuffed giraffe and he doesn’t tell anyone at all about it, because that it is what a secret is, something that no one knows except you. Shhhh.

I think you might like...

Radar Beach

Joseph reaches down and picks up a shell. He hands it to the boy, who is dragging a red plastic bucket across the sand. “Here. What about this one?”

Bill assesses the offering intently. “No Daddy,” he says firmly, “It’s broken here, see.”

Logic Unfolding Across A Colourless Void

It is late when I see you moving into the flat above the pub opposite. Must be past 11, because I hear the doors swinging open, hot blue noise gulping for air.

Wetware, Rattle And Heddle

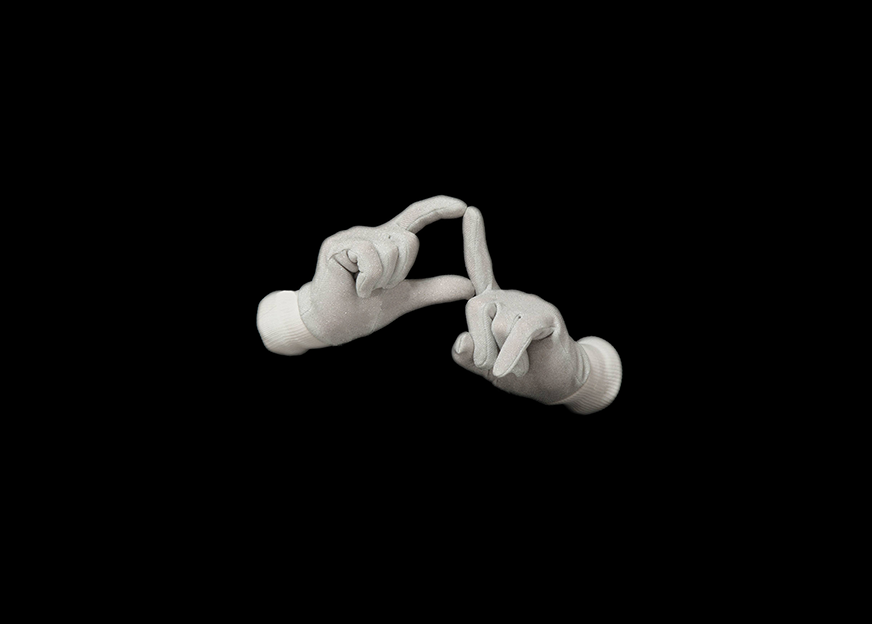

“And this is the sign for asleep,” says Alison, closing her index fingers and thumbs together in front of her eyes. “Go to sleep now my darling.”

She smooths out the duvet cover with her hands, uncreasing the printed astronaut suit, flattening the stars in their cotton void, repositioning the blue Earth from sliding off the side of the bed. She kisses Bill’s hair, feeling his fragile skull millimetres away from her lips. “Night night.”

“Night night Mummy,” he says.