He is a red man all over, everyone can smell it. Even through the jasmine oil I apply so liberally before each shave he reeks of rusty iron and musk like the heavy gate to the bull’s field that was left open last year. I prattle on about the weather and tug my comb through his beard with my fingers crossed. Every time I snag on a knot I wince, afraid by the size of his huge hairy fists and the bulk of him sprawled across my biggest chair.

I am halfway through the shampoo when he speaks. ‘Blue is the opposite of red’, he says. ‘And my wives like it’. He laughs and the sound is tight as a drum in my stomach. I nod as the lather turns blush pink, then scarlet. I have to swill out the sink many times before it is white again. Afterwards my food tastes of patchouli pomade for days but the salon stinks of rancid meat. I call in the rat catchers who lay traps underneath the counter, behind the pot plant and in the back of the store cupboard. We catch nothing but hair and dust. The rat catchers scratch their balding heads and sniff through their long noses as I count out the money from the till. Neither of them has any need for my services. I buy air fresheners for all the plugs and switch them to maximum.

On his next visit, there is a new ring on his left hand. I think about the proud new padlock on the gate to the bull’s field and the rotten roses still tied to the fence post, their sad plastic wrappings torn in the north wind. He smells bad but appointments are down and I can’t ask him to leave. I catch his eyes in the mirror watching my discomfort. However gentle I am, my fingers tangle easily in the wiriness of his beard. He hisses and grabs my wrist, leaving a band of dark blue bruises that matches the dye stains on my fingers.

My regulars stop coming. They can’t stand the stink anymore, they say. It is seeping into their clothes and can’t be washed out. Their wives are refusing to lie with them. They burn the clothes in piles, all around the town, in backyards and allotments, in ginnels and on cobbled driveways. I take everything out of my wardrobe and burn all my dresses, shirts, shoes and underwear on a scrubby patch of grass out back until I am looking at a pile of ash. I inhale the smoke, hoping to cauterise whatever is festering inside me. Everywhere smells of charcoal and barbecued liquorice except the salon. In here it smells like the stand-off between the bull and the men with the bolt gun.

I call in the plumbers who take up the floorboards and find nothing except a stack of old newspapers so brittle that when they hand them up to me the paper turns to confetti. It fills the salon with tiny letters that fall all around us. The plumbers look at me under bushy eyebrows and shrug as I hand over the money from a tin box I keep for emergencies. It takes three bin bags to clear away the confetti.

I borrow from the sky and paint the walls a pale grey blue. The vapours give me a headache and I prop the door open to sit on the step drinking tea with bitter pills and reading the paper. There is a picture of him outside the town hall, towering over his new bride. This would not be news but for the fact that not much happens around here and he has been married more than once before, though no one, not even the reporter, can quite remember the details of his previous wives’ names, when they were married or what terrible calamities have led to him being repeatedly widowed. His beard looks magnificent, even in black and white.

I go to the local records office and ask to see the register for the last seven years. It is better than being in the salon where the new paint smell is wearing off, giving way to the putrid stench that now clings to the air all across town. I run my fingers down the pages and stop at his name six times. His wives have pretty names that bloom on the paper like fresh spring flowers. I shut the book and return it to the tight-lipped woman at the high desk. Her spectacles are cloudy but she does not take the cleaning cloth I offer her so I use it to dry my eyes.

Back at home I sweep the floor and carefully place cuttings of his hair onto the photograph from the newspaper, which I wrap inside a sheet of paper listing his six pretty marriages. I tuck the edges under as carefully as a packet of meat and place it under the floorboards for luck. On my hands and knees I scour the place, sloshing bleach into the darkest corners of the salon until my skin itches and flares. Soon enough he is here again, sitting in my chair, smelling of knives and mirrors. He is as red as a fairytale this man but he is my only client now so I need him to keep coming. I massage his skin with the jasmine oil, feeling his jaw beneath the beard. I pull the comb, inch by inch, through his thick hair that is as matted as a cowpat, but he does not touch me again. There is another ring on his left hand. They are stacking up.

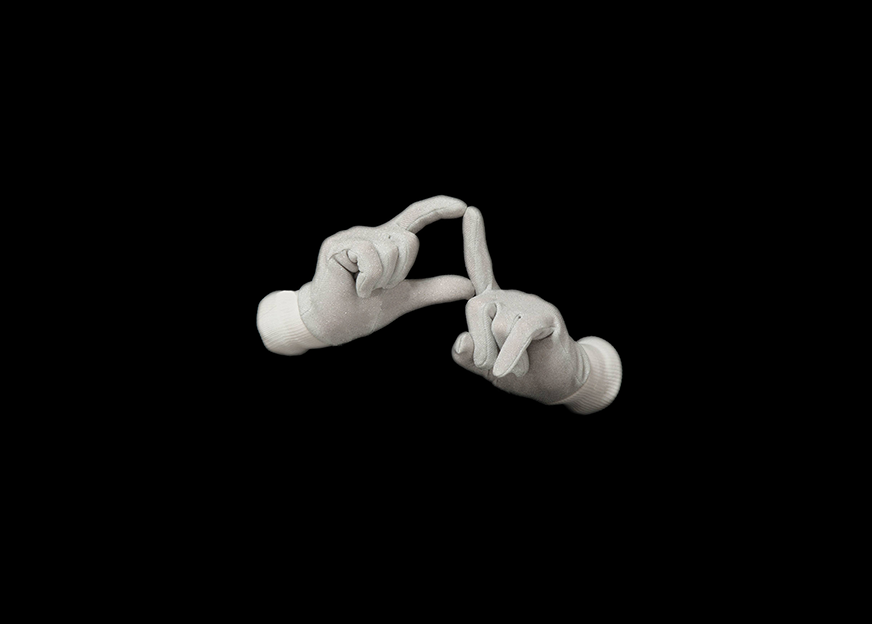

I wash the red out of his beard and clear my throat, wanting to ask a question. I do not. He relaxes back into the chair as I bring the bowl of dye forward. Gloves on and brush in hand, I paint, working into the roots that disappear into his face. I paint, we wait, I rinse and shampoo again. Perhaps if he let his beard grow white he would be powerless. I press the razor against his neck, feel the pulse of blood under the skin. I think of the bull hanging from its nose ring in the abattoir, jerking violently as the last drops of blood drain from its throat into the sluice. His hair has poked holes in the gloves and my hands are stained with ugly blue blotches. I rub the patchouli pomade into his beard and step back. It makes him look distinguished, this indigo black beard, hiding his throat, his mouth, his secrets in the darkness, but his pores still ooze with the affront of an open casket in mid summer.

I walk to the gate at the bull’s field and lay a posy of forget-me-nots on the ground. Into the broken air I whisper his wives’ names over and over and over again. With my fingers crossed tightly.