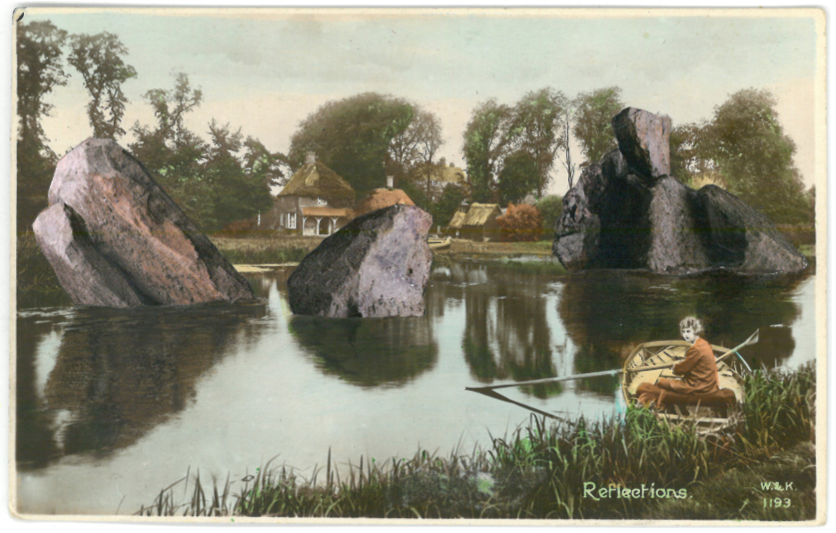

Anxious Chronicles (2010-ongoing)

The past and the future redrawn in the present. In this ongoing series, collage, paint, pencil, crayon, print and thread subvert original postcards dated 1897-now, creating new lived experiences.

Investigating the life of things across space and time

Podcast for Fermynwoods Contemporary Art; 52.08mins

Sarah Gillett interviewed by Jessica Harby

This podcast will feature artist talks, discussions, original commissioned sound art and audio essays.

When we began planning the podcast in 2019 as an extension of our programming, we thought it would be great to treat it as a kind of audio gallery space, one that’s fully accessible from people’s homes. Especially as our in-person venues and sites tend to be rural and sometimes difficult to get to.

We wanted to bring something special to those who couldn’t travel to experience our in-person talks and exhibitions.

Well. As I’m recording this in April 2020, that’s currently most of us, as we shelter from the COVID-19 pandemic. I speak for everyone at Fermynwoods when I say I hope this finds you well and safe and taking care of both your physical and mental health.

I’m pleased that this first episode is a talk with Sarah Gillett, a featured presence in our two-year programme In Steps of Sundew. Sarah Gillett is an artist and writer investigating the life of things across space and time, as well as across media. We heard a bit of her sound piece Well Well earlier, constructed from 20 audiobooks of Alice in Wonderland, and will be listening to another sound work at the end of the talk.

In what I like to call The Before Time, we commissioned Sarah to produce artworks for multiple sites across Northamptonshire over the next two years. We’ll be talking a bit about the work she’s started for those exhibitions, as well as her overall practice.

We’re happy to have you and hope you enjoy.

To make the podcast as accessible as possible, this is an edited transcript of the live conversation.

Jessica Harby (JH): Hi Sarah, how are you doing?

Sarah Gillett (SG): I’m ok. It’s a beautiful day today and obviously quite a strange time at the moment. But it’s apt because I’ve been thinking a lot about dark spaces and negative spaces, and turning those into a place where we can connect in a different way. Which actually links really well into the work that I’m making at the moment.

JH: How are you managing to be so creatively productive right now?

SG: It’s a funny thing, isn’t it? I think although it’s challenging, a lot of what I’m interested in is about slightly unusual circumstances or bizarre encounters of some kind, it’s actually a really interesting space in which to be making work. For a long time I’ve felt that the kind of work I make – my working style – has been deeply unfashionable, and then suddenly I’m finding that making work about ghosts and meteorites and science-fiction-y things happening to the sea, is suddenly almost part of our living world. Especially in the piece of writing I’ve been doing in the moment, I’ve been looking at what astronauts dream of when they’re in space…

JH: Based on fact?

SG: Based on fact. I’ve been looking at different sleep research and sleep labs’ research with astronauts, and what’s interesting is that the longer astronauts are in space, on the ISS or if they’re going and doing some stuff in their world, the longer they’re out of the atmosphere of our planet, the more they dream of our planet. And so the dreams that astronauts have are very mundane, they’re about ordinary, domestic things. I like the idea that in this very extreme environment, the mundane is the thing that is jarring. I know from myself and other friends, and even research being done on people at the moment about dreaming and sleeping patterns in this very strange moment – people are remembering dreams more vividly. Whether that’s because people aren’t sleeping as well or whether it is a sense of uncertainty, I don’t know, but I think it’s really interesting to think about how our external environment leaks into our subconscious and what happens in our imagination without us necessarily wanting it to. But equally that can be a great spring for creativity and for new thoughts that otherwise we wouldn’t necessarily have had.

JH: It’s interesting you mentioned that the rest of the world’s almost caught up with you and your headspace and what you’re interested in making art about. You sent me your audio work Well Well, which I had heard before, but what really struck me about it is that it felt so current, because it is about being lost in a never-ending moment. And of course right now we are all suspended in a kind of collective moment which will have an end, but the end is certainly not in sight or anything that we can plan for. Is the astronaut dream work something you were researching before lockdown? Or did that come after?

SG: I started researching it probably a month before lockdown, but ideas around night, the landscapes of the night – whether that’s a physical landscape like the moon, or the landscape of dreams, the things that we think are there in the night – are always present for me in my work.

I’d started looking at astronauts’ dreams and then, with this situation, I tuned into a little strand of the news around dreams and what’s happening in people’s subconscious at the moment – and mental health. So it’s interesting for me to actually be able to contextualise what I’m always thinking about in a new environment. We’re all in our own little pods at the moment. It is a little like being in the experience of an astronaut because we’re limited in terms of our daily experience – especially if we don’t have gardens or yards to sit out in. If we do have a window then we are looking out at the world, but it’s mediated, we’re not able to physically touch it, or each other.

The weather has been so beautiful mostly during this time as well – the colours are so vibrant, the tree outside here has just blossomed. There are beautiful trees with all their fluffy blossom everywhere and then that lime green with the new leaves of the trees, and it’s incredibly intense with that blue, blue sky. It’s made me think of, again, the first time an astronaut looks back at our planet in space, and what that experience must be like. It must be for some people a very profound, life-changing moment to see our planet and the blue and the clouds, from that distance and to recognise the value of it.

That experience for astronauts is called the overview effect, because it’s a moment of contextualisation – of realisation of our very, very small individual place in the universe. It’s almost incomprehensible how we could be part of this beautiful, magical world that we can see in front of us but can’t actually touch and are separated from.

I do feel we’re all probably eating different things than we would do ordinarily, there are things we can’t get, we are speaking to friends and family and loved ones on Zoom and recording ourselves, possibly, but not to have that physical interaction I think is the biggest difficulty for me. It’s just very different sitting with somebody. I live on my own so there isn’t anybody else here. It makes me think of people that are in isolation all the time, whether by choice or not, and it makes me value our world and the worlds that we create for ourselves.

Even though I love being on my own, I’ve built my own world with objects and plants and books and all sorts of strange things, but I think I underestimated, stupidly, how important people are.

JH: I don’t think that’s stupid. I think that’s one of the bright spots that people are experiencing during this. I’ve also experienced that kind of shock at the almost surreal, vivid outside. Does this astronaut research that you are doing tie in at all with the work we commissioned you to do at Fermynwoods?

SG: At first I hadn’t connected the different bits up, but the more I’m thinking about the work that I am making for Fermynwoods the more I think it will come in.

JH: Just so our audience knows, Fermynwoods approached you last year about our new In Steps of Sundew programme which would involve you responding to multiple physical sites across Northamptonshire, including Fineshade Wood, Rockingham Castle, East Carlton Park and parts of Corby. We were so excited about commissioning you throughout the two years because your artistic output is wildly diverse. You’ve done drawing, collage, audio, performance, writing and so much much. I was really interested in what might happen if we just unleashed your brain on these places. I know you had a couple of meetings with staff at Rockingham Castle before the lockdown. I was wondering if you could talk about your approach to that site specifically and what about it inspired you.

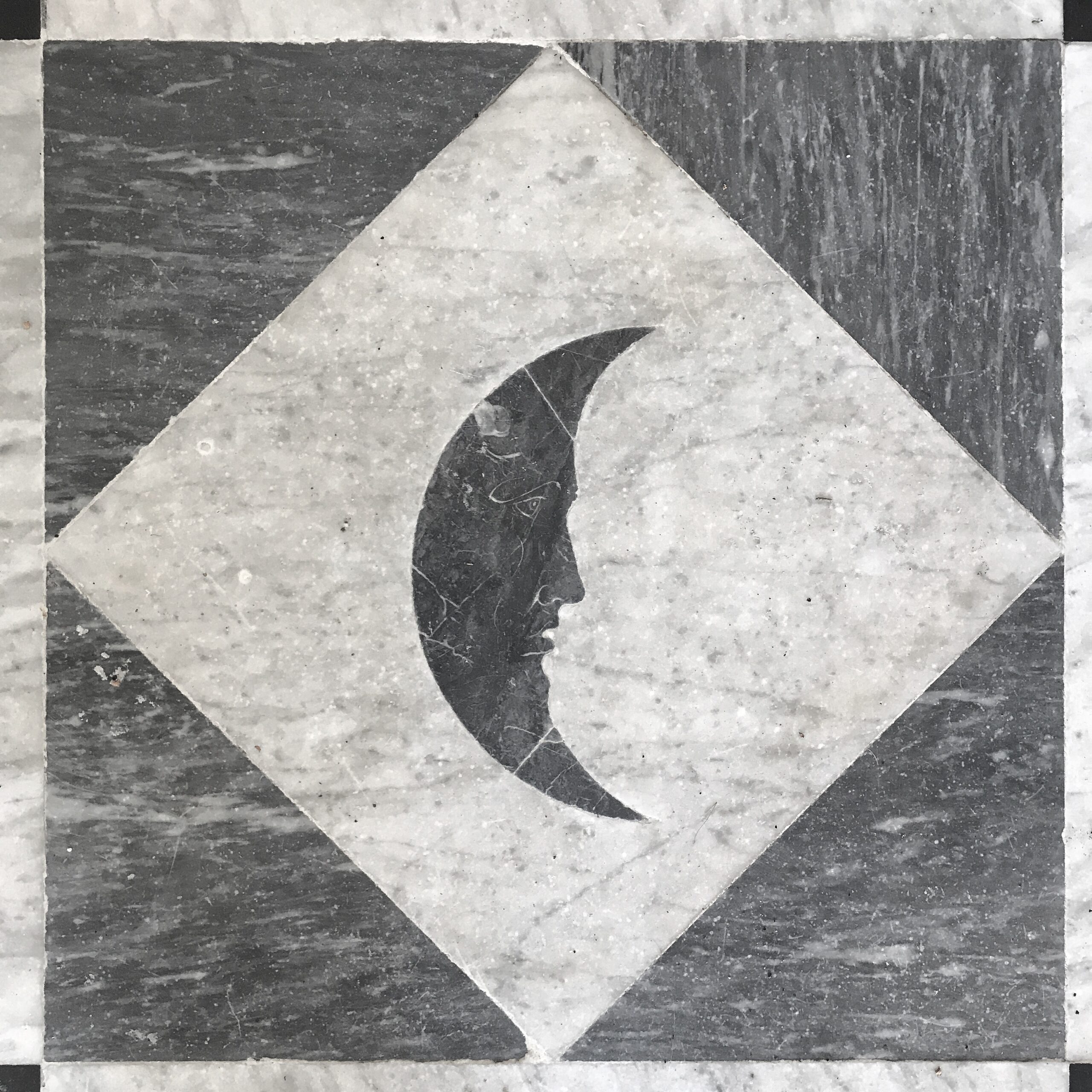

SG: Going to Rockingham Castle was like being Alice in Wonderland. It’s the most fantastic Norman Castle and has this amazingly rich history. On the top of a hill, if you look one way you can see the sun setting and then if you look the other way you can see the moon rising. It has this incredible vista of the sky, these beautiful planted gardens with yew hedges, and then this incredible space that has obviously changed and been adapted and built on. Parts have been knocked down and other things built over the top to make layers of history.

I’m really interested, as a woman, about what we leave behind, especially in places that are perhaps carried through a male lineage. So when we think of stately homes and the Royal Family, we’re talking about places where often the wealth and status is carried through the man, and the possessions, the decisions that have been made have often been made by men. So when I went to the castle, I specifically wanted to know about objects and belongings and things that had been left behind by the women who had lived there. What influence those women had on the feel of the castle and what they did in their daily lives – but also how they potentially changed the people around them and what their legacy was.

What was brilliant was that because it’s such an old space and everything has been so carefully kept and preserved (there’s an amazing archive that I’ll talk about in a minute), there were some fantastic women for me to look at. Two I immediately gravitated towards, one being a woman called Lavinia Watson, who lived in the castle in the 1800s and was a confidante, with her husband Richard, of Charles Dickens. Dickens stayed with them often and actually wrote David Copperfield whilst staying with them – the novel is dedicated to Richard and Lavinia.

While there Dickens would often wander the gardens in the evening, like we’re all doing now after we’ve finished our working-from-home day. There’s one particular part of the gardens where there’s an amazing yew topiary hedge that looks like elephants, a parade of elephants trooping across the Northamptonshire countryside. On one occasion, Dickens thought that he saw a figure – it was there and then it was gone. He wrote about this experience and turned it into a character for his novel Bleak House. So, from then on, this part of the garden became known as the Ghost Walk. Lavinia wrote to Dickens a lot and they exchanged correspondence. For a start I’m interested in the actual physical letters, the physical ink on the paper and the identification of somebody just through their writing – seeing that it’s a very very personal set of objects…

JH: And you’ve had access to the archive at Rockingham?

SG: The letters between Lavinia and Dickens are reproduced in the castle itself, so if you visit you will see a case that has some of these letters in it, and then you can request access to the private archive, which I was really lucky to be let into. The archive is kept by a wonderful man called Basil who is in his 80s and has worked in the castle for 27 years – forgive me Basil if I have got that wrong. Basil used to be a history teacher and knows everything there is to know about the castle. The archive is not a huge room, maybe the size of my flat, but it’s full of these cardboard boxes very neatly stacked on shelves, and inside are treasures of the past. It looks kind of mundane, but then inside you have all these wonderful, wonderful things. Her letters, the original letters, are in the archive.

There’s another woman called Florence who lived in the castle in the 1900s. In the 1930s after the First World War a lot of people went to mediums and spiritualists to try to talk to their husbands, sons, fathers – all these thousands of lost loved ones – it was quite a big fashion. Florence went to a lot of seances which were often held in the little church next to the castle with the local parson present, so it must have been quite an interesting gathering. Having someone in that space who is religious alongside people there who could potentially clash over beliefs and intentions, but they don’t seem to.

What was wonderful is that Basil was able to show me these typed-up transcripts of the sessions, the seances, which just read like plays. They are just like found art as they are. There’s stage direction, there’s different voices, they’re laid out like playtext, and the copies I saw are on waxed, thin pieces of translucent paper that kind of crackle when you hold them. I said to Basil “I even like the paper that they’re typed on.” And Basil said to me, “Well you see these are the flimsy copies.” I had never heard this term before, and he told me that when they were typed up there would have been the original copy, the nice copy on the thick paper, and behind that you’d have your sheet of carbon paper, and behind that you’d have this thin, thin paper. So you would have two copies, and the thin version was called the flimsy copy. Within these moments, accidental sentences and interrupted thoughts, and coincidences, I just hooked onto this phrase because the idea of copies, copies of things, is always very present in my work.

I’ve got an MA in printmaking and the way I come into printmaking is through an idea of storytelling. The idea that, say, we’re at an amazing summer party. There’s one party, but if there are 200 people at that party, everyone takes away a different copy of that party away with them, in themselves. And every time somebody talks about that party to somebody else, there is another copy of that party made, because every time we tell a story it changes slightly and it shifts. I imagine that we’re taking prints with us in our heads through the world, and that’s the way I came to printmaking. So this idea of the flimsy copy, the copy that is not the original but is in itself an object and is true and valid and is as real as the big, thick, lovely copy really resonated with me.

And of course I’m interested in the flimsiness – the flimsiness of what is real, what we see our meaning being in our lives and how our existence is so fragile. Especially because I was thinking about night, and in this context of the seance and the absence of something, whilst at the same time trying to recall a presence, it really made a connection for me. So I started to develop this work that I’m in the middle of at the moment, called The Flimsy Copy.

I’m really thankful that I got to go to the Castle before lockdown, because it means that I had material to work with. A lot of the thinking is still going on in my head, which is why I’m slightly hesitant when I’m talking, because for me the work comes out of the process and out of the research with these little snippets of things that fit together. So I don’t yet know what the work is going to be or what the story is that I’m trying to tell through this material.

I do know that one of the pieces will be a story show. I’m hoping that I’ll be able to be in a room in the castle, probably in the evening, with an audience of people together with me, and perform a story which will include sound and images. In thinking about the soundscape for this, I really wanted to try and make, and then learn to play, the theremin, it obviously being an instrument that you don’t touch. There is a division between the object and the person, but it resonates as a sound and an atmosphere through the presence of an interaction between the body and it. It was making me think of the seance trumpets and the other paraphernalia that mediums may have used.

JH: Yes, it was really good to connect you with Stuart Moore, who is currently one of our Education Coordinators. Earlier in the year he ran a workshop called Human Theremin which involved two people operating a theremin – so you’re really playing the other person rather than playing the instrument. On the day we had a group of people – some of whom had never met each other, doing little finger flutters at one another and making weird high-pitched noises, I got so excited that I had to sit down.

SG: Yeah he’s really wonderful – he sent me the pieces for a basic theremin that I could assemble and start playing, but also went far beyond my initial hopes to suggest new ways of working, and I’m hoping that together we’ll put together a soundscape for The Flimsy Copy.

That collaging of people together fits in with the way that I work, too, as much of my work is about bringing fragments of things together and collaging them – whether that is in sound or in postcard interventions or tapestry or whatever it is. So it was just the perfect connection, I think.

We’ve obviously talked about the material of the women in the house, but also going back to the outside and the night sky and how we navigate it, particularly at Rockingham because of this wonderful vista it has, I’ve been thinking a lot about the weather.

I have a little tiny book here called The Observer’s Book of Weather, which is one of those small, pocket books that has a pale blue linen binding with the words embossed into it in a dark blue – it was printed in 1955. What’s lovely about it is of course a lot of the science in it is no longer relevant or has been developed since, but the language and the words that are used are incredibly evocative of an experience of the world and very poetic. For instance, at the same time as Florence was holding these seances in 1935, there is a passage in this book that says:

“In March 1935, blue rain was reported from the Shetland Isles after a heavy thunderstorm and was described as looking very much like blue black ink diluted with water. The explanation of this was given as being due to the particular atmospheric conditions in that locality, which at the time were highly polluted. These conditions were extremely unusual as there was an unstable air above a stable layer, combined with a mass of cold air previously moving in the opposite direction. Even in the early stages of the storm, the warm air was three quarters surrounded by cold air, the latter having arrived on the south-easterly wind.”

There’s something in that writing about the air and the surrounding of the air that makes a presence within it, a body, that is only air but a different temperature from the other air. Often when we hear of mediums and spiritualists or ghost hunters, there’s talk of temperature, of how suddenly the room has got very cold. I think there are really interesting connections between a scientific understanding of the world and an emotional one, and that if those things can be brought together into something then perhaps it gives us a fuller reading for where we are, and where we place ourselves. That might be an uncomfortable place, we might think it’s nonsense, or we might not believe, or we might very heavily come down on one side of the other, but actually all of it is part of our experience. Especially now, there’s lots of things coming into people’s consciousness and subconsciousness that before perhaps they never even would have entertained.

JH: I think that leads quite nicely into the second audio work that you’ve been so generous to allow us to play as part of our podcast. Would you mind introducing it and just telling us a bit about it before we listen to it?

SG: This, I think, was the first “proper” audio work that I made. It was 1996. It was the first year of my BA and we were exploring the idea of aural and oral landscapes. I made a whole body of work with different writings and then I got different people to read and had a sort of performance night.

The work you are about to hear is called Black Night. I really wanted to make something that wasn’t metaphorical in any way. I wanted the connections between the words to be just purely descriptive. There are a couple of anomalies in it, because I felt like it needed something to shift in it slightly towards the end. But as you will hear, we have “black night”, “blue light” “pale face”, “dark space”. They’re very, very simple words, and it’s a chant, with these words repeated over and over and over again.

When I recorded it, I remember it was a weekend and I had gone into college and there was a friend who was there as well, he was a musician and he had a little 8-track with him. I asked if he’d mind experimenting and recording this thing with me. And we did. I recorded the main whisper that you will hear throughout, which is just over seven minutes, in one go. It’s really hard to whisper something at the same tempo for seven minutes without stopping. And then he recorded two more tracks and I recorded another track on the top of that, and then we added sounds and other things in the background. Each of the tracks was recorded in its own channel, in one sitting, and I kind of popped it all together.

It’s a dark space, it’s really designed to be played with the lights off, pretty loud. It starts really quiet but it does get loud towards the end. You will hear that it is a little bit fuzzy, a little bit hissy, because it’s not a digital recording, it’s an analogue recording from back in the day. I could have tidied it up and cleaned it, but I didn’t want to because part of the atmosphere of it is about the kind of air around it, like we’re saying, so it becomes a kind of presence in the middle. It’s about whatever you want it to be about. I hope you enjoy it. Put your headphones on, close your eyes, and breathe.

JH: Thank you for listening to the Fermynwoods Contemporary Art Podcast. This episode received support from Arts Council England and the Kenneth Fund. You can find Sarah Gillett on her website sarahgillett.com, and she’s @inkystudio on Instagram and Twitter. Follow us @Fermynwoods on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Visit fermynwoods.org for more on this podcast episode and to sign up for our monthly email newsletter. Thanks for listening. Hope to see you back here soon.

The past and the future redrawn in the present. In this ongoing series, collage, paint, pencil, crayon, print and thread subvert original postcards dated 1897-now, creating new lived experiences.

The first audio work I made, this chant references the moors where I grew up and the mythologies embedded in this landscape.

Down, down, down she went. Could not stop herself falling…

This audio collage is constructed from 20 versions of the ‘well scene’ in audiobooks of Alice in Wonderland. It is not about Alice, but is an exploration of falling and feelings in sound.

Sarah Gillett is an artist and writer from Lancashire, UK.

She currently lives in London.