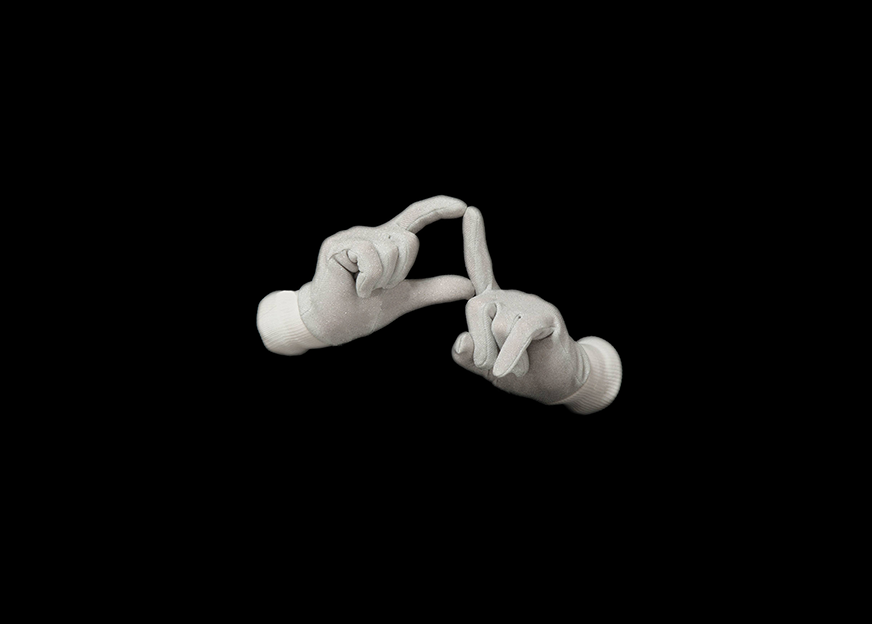

“And this is the sign for asleep,” says Alison, closing her index fingers and thumbs together in front of her eyes. “Go to sleep now my darling.”

She smooths out the duvet cover with her hands, uncreasing the printed astronaut suit, flattening the stars in their cotton void, repositioning the blue Earth from sliding off the side of the bed. She kisses Bill’s hair, feeling his fragile skull millimetres away from her lips. “Night night.” “Night night Mummy,” he says.

“There you go,” says Sophie, splashing white wine into a tumbler. “It’s very drinkable. I’ve eaten nearly the whole bowl of crisps, sorry.”

“Delicious.” Alison holds the wet, cold bottle against her temple. Her brain hurts. “There’s loads more packets in the cupboard if you want. Helen’ll be here soon – let’s go next door.”

“Shall we have some music?”

“Go ahead,” says Alison. She passes her laptop to Sophie, its warm, brushed metal sheathing almost soft in her hands. The environmentally friendly MacBook Pro family is made from highly recyclable aluminium with a mercury- and arsenic-free LED-backlit display. “Computers are weird,” she says as Amy Winehouse’s dead voice scars the air with vivid splotches of life. “They’re like alien objects. We’ve just got used to having them around, but they don’t really belong here.” Trillions of black holes in people’s homes all around the world, portals into infinite space.

Sophie laughs. “Maybe it’s us that don’t really belong anymore. God, imagine having to use a typewriter at work. And not having any Asos.”

“The digital me has a much more interesting life than the real me,” says Alison. “Really all I want to do is stay at home –“

“- sewing and knitting and baking. Come off it Alison,” says Sophie. “You’d go mad in about a week and end up in the attic like Mrs Rochester.”

“I was going to say that I want to have more time to make my work, and yes, I like cutting old things up and trying to make new things from them. Re-stitching and collaging back in. It’s the way that I think – nothing is fixed. Everything can be changed, re-worked into a new pattern. Look at the past year.”

Sophie looks at Alison. “Is there anything you want to tell me honey? I’m worried about you. We all are.” There is something, I know it.

“He called me Mummy tonight,” Alison says. “He’s never done that before.”

“Poor kid.”

There is a brief moment of silence as both the women and the singer pause, as though they are all being directed in the same play and this is the slanting second their story arcs are timed to synchronise.

On the wall the photograph looks at her. It has a way of looking at her that she will never get used to because it is the rocks that are doing the looking. The woman in the photograph is from another time, her arms held awkwardly in place by iron rods, as though without them she might fall, or jump. There is a knock at the door. “Alison?”

Nothing is ever black and white. Like the rocks, it’s all shifting shades of grey – silver, graphite, lead, aluminium, slate, mercury.

“I’ll be right there,” she says. Wherever that is.

They push the sofa against the wall and lie on the carpet, looking up through the glass at the black sky.

“I can see you,” says Sophie. “And me.”

“Do you mind if I smoke out of the back door?” Helen leans over a candle, her face illuminated, her head turning away.

“In the stars or in here?”

“Well, both. Turn off the fairy lights whilst you’re up, would you Helen?”

“I never thought I’d end up in a house with a conservatory,” says Alison. Or with someone else’s child. Especially not his. “So I tried to make it like a Rousseau, you know, that painting with the tiger in the forest? Hold on a minute, I’ll find it on my phone.”

“It’s wonderful,” says Helen, bringing spring frost and fag smoke back in with her. “It’s like being in a secret garden.” Tree ferns curl above them, gunnera casts wide plates of shadow, plump mosses absorb light and water on the banks of the artificial stream.

They lie back, heads together, and look at the bright little screen. “He was a tax collector,” says Alison. There’s always a price. I am paying my dues.

“Look, look, shooting stars,” says Sophie.

Alison, Helen and Sophie gaze up as the Earth passes through the debris stream of a comet, the atmosphere igniting a hundred tiny particles of dust and ice to etch the light of countless parables across the night sky.

“Amazing,” says Alison, grasping hold of a table leg as an anchor. “Gives me vertigo every time I see one.” The fear of mortality, the small dizziness of not knowing.

“Do you think that one’s going to hit?” Helen points at a flare drawing closer, its stream low and unstoppable.

“God, maybe we should call someone,” says Sophie. “It’s pretty close.”

And they scramble to their feet as suddenly a white blank light bleaches away all shadows and three-dimensions, the silhouettes of trees and houses, the contours on faces, the colour of hair, skin, clothes, eyes. Objects flatten and become vibrating paper cut-outs, holes punched in card swallowed up in echoes as all the windows in the glass house rattle and expand in their frames, shattering outward in a single ringing call. Afterward the only sound is a soft patter, light and gentle as the touch of fingertips on skin, as millions of tiny glass cubes settle on the lawn in pixelated crystal snowdrifts.

Alison opens her eyes.

“Sophie? Helen?” My side hurts.

“I’m here, we’re both ok. Helen’s gone to check on Bill,” says Sophie from near the kitchen door. “I think everything’s fused.”

Alison sits up carefully. She can just make out Sophie, feeling her way round the palm trees. The floor looks ruffled.

The conservatory is reduced to a delicate construction of twisted metal bars. Against the dimmed lightbox of the sky the plants stand tall and black, glossy leaves shifting slightly in the night breeze, grasses whispering. She imagines years into the future, ivy covering the frame, tendrils stretching across the empty open gaps. It is very dark. No ambient streetlight reflected against cloud, no domestic overspills from neighbours’ bathrooms or bedrooms. No moon.

“Bill,” she says. “Laura – I will never forgive myself if –”

“He’s fine,” says Helen, appearing from the lounge, phone torch on. “Still fast asleep. Oh God, Alison, you’re hurt. Let me see.”

Alison looks down at herself in the torchlight. There is a wide tear in her dress, the edges frayed and singed. A long fat welt, already dark blue, runs from her ribs to her hip. “Oh,” she says. “Ow.” My hands are trembling.

“It’s quite a bruise Alison, but it hasn’t split the skin. Do you want to call Laura?”

“No, I think I’m ok so best not worry her. So much for our romantic weekend. Ow.” I can’t stop shaking.

Helen feels around Alison’s abdomen. “Well, no broken bones, but we should get you to hospital to check you out properly, and we’ll have to call the police. I can still take Bill for the weekend so you two can at least get some rest. You’re going to be tired once the adrenalin wears off.”

“What was it?” Sophie finally makes it over to them with a navy blue felt coat that she tucks around Alison, holding her close.

“That.” Helen shines her torch at a rock embedded a foot deep into the floor. It is fringed by rectangular tiles upended like dominoes in leaning concentric rows, thirty deep, collapsing onto themselves at the outer circles. A circular warp around a heap of chaotic matter. The rock is roughly the size of a coconut, its grey surface pitted, worn in places. It is looking at them.

Alison starts to laugh. “It’s a meteorite. I’ve been hit by a meteorite. What are the chances?”

She laughs and laughs and laughs.