I am not the only one. Knowing the skies has long been connected to locating ourselves in the world. We mapped what we saw and placed our fixed stars on a giant celestial sphere that revolved daily around the Earth. We drew lines between the holes in the firmament and made pictures that we called constellations.

A French man once said to me “Haven’t you got a lot of stars…” as he traced his fingers across my skin, lightly up my arm, across my clavicle and down my back. The skin is the body’s largest organ and I am adorned with freckle clusters and moles from head to foot.

In fact, no celestial objects are fixed to each other and since stars have their own independent motions, our constellations are changing slowly through time. After tens to hundreds of thousands of years, the familiar outlines of our starry drawings will become unrecognisable as though the skin of the universe has stretched and sagged with age.

The word desire originates in the Latin word sidus, meaning star. De sidere, or ‘from the stars’ carries within itself a long journey, patience and anticipation far beyond a human timeline.

I lie on a lawn looking at the sun through a pair of cardboard and black polymer glasses. The eye’s retina lacks pain receptors and even from 92.96 million miles away the sun can damage eyesight in as little as a few seconds. Sunspots appear as dark shadows floating across the surface like the wavering negative dots I see after the flash of a camera. Sunspots are a temporary phenomena, cooler areas caused by a flux in the sun’s magnetic field. Some are bigger than the Earth. I roll the words umbra and penumbra around my mouth. It is not the last time these words will cast a shadow.

Even before we are born, sunlight is key to the development of our eyesight. It’s very dark inside the uterus, but when a pregnant woman bathes in the sun some photons of light still make it through to the foetus. Babies of women who live at the northern latitudes and become pregnant during the darkest months of the year are at an increased risk of eye disorders.

The word locate traces back to a word of uncertain origin, stlocus in Old Latin. In a universe that contains billions of galaxies, each containing millions of stars, where am I to place my body?

Planet means wanderer in Ancient Greek. I go to a museum in Paris to study astronomical clocks, planetariums and orreries. It is raining but romantic. An orrery is ‘a place for planets’; a mapping device that houses the night sky. The orrery is a globe spinning beneath my fingers as though I am outside of time and space, not within it. To see the sky as on Earth I have to project myself inside the orrery, inside the body.

I carry this map both on me and in me. It stretches, contracts and moves as my body changes.

When I look at myself, I see stars.

The pigment melanin, from the ancient Greek word for black, is stimulated in foetuses at the same time as our eyes are formed, before our bodies grow limbs. Around one in a hundred babies are born with nevi, or congenital moles, which can vary in depth of colour from blue, blue-grey, blue-black to deep brown, milky coffee and tan. Many nevi are invisible at birth, hiding under the skin, waiting for sunlight to activate them. Over the first few months of our lives, light stimulates the production of melanin to fix the colour of our irises and expose the clusters of colour that are inherited from the beginnings of life.

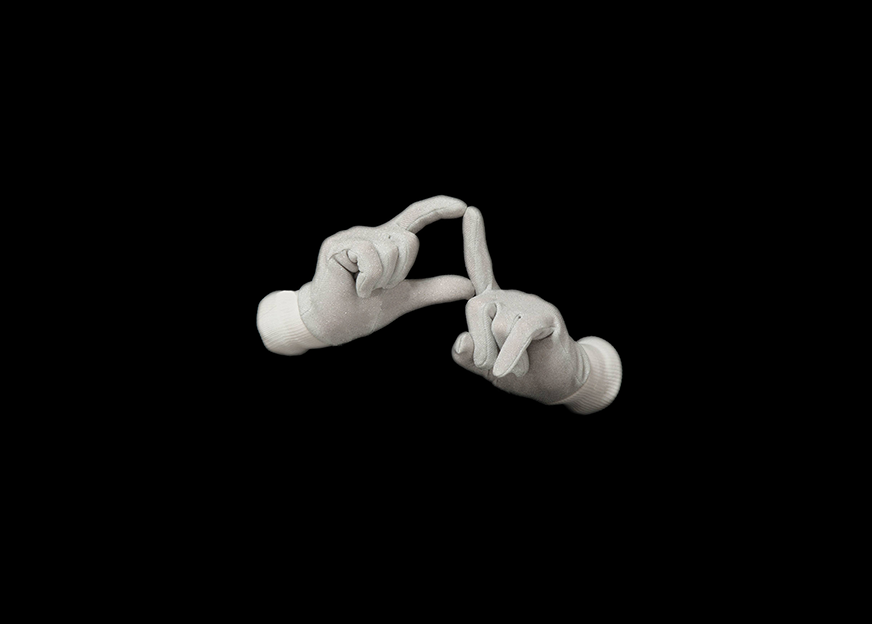

Because the production of melanin begins so early in foetal development, our limbs interrupt and scatter the pigment that lies latently under the surface. Nevi do not exist in isolation – larger moles split in two, three or four. If I place my forearms together, my legs together, place myself in between two mirrors, there are twin stars on my stomach and lower back, on my left and right thighs, on my upper arms.

I lie in the bath and look at myself. The round parts of me break the skin of bubbles; the water laps at my breasts, my stomach, my knees, the tips of my fingers and toes. Underneath the water my body is invisible. The event horizon of my belly button pulls water down into its depression, finding the puckered folds that I have never explored and so do not exist to me. An early meaning of the noun ‘depression’ was ‘the angular distance of a star below the horizon’. Inhale. Sink. Submerge. I open my eyes. Above me the surface of the universe fizzes and pops.

It is the day after the winter solstice and the full moon lasts for 15 hours and 34 minutes, the longest since 2010. I lie on my back and look up. We are face to face. Exhale. My breath is white and cloudy; the water inside me that is usually invisible. This is the Full Long Nights Moon, the Cold Moon, the Frost Moon, the Elder Moon, the Moon When Deer Shed their Horns, the Moon Where the Sun Comes Home to Rest. It brings high tides and fish in great numbers. Waves crash against sea defences and rip down cliffs. Two great lunar craters are visible, Tycho and Copernicus.

A moondial is only accurate on nights of a full moon. Every other night the moondial spills time forwards or backwards, so one week either side of a full moon the moondial will read 5 hours and 36 minutes before or after the proper time. Under the moon I walk in the garden and tend to my night-blooming plants, full and ghostly in this reflected light.

The word consider, to regard in a particular light, literally means ‘to observe the stars’. The Romans were obsessed with divination by astrology.

I consider myself, flat on my back, star-fishing.