Investigating the life of things across space and time

The old fart in Room 17 is becoming a problem. He does it even when his wife’s on the terrace, sweating, counting her rosaries. Clack-clack. Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. Ah, Mamma, what would you say if you could see me now? Four stringy children and a fat pig of a husband who belches triumphantly after every meal and snores all night. Clack-clack-clack.

The crowd watches as she walks forward and unthreads a pale rose. Its thornless stem, shaven into meek concave depressions, fits her fingers.

Joseph reaches down and picks up a shell. He hands it to the boy, who is dragging a red plastic bucket across the sand. “Here. What about this one?” Bill assesses the offering intently. “No Daddy,” he says firmly, “It’s broken here, see.”

The problem was how to kill them. There were many possibilities. With a rough, heavy stone or a small, sharp knife pushed deep through the skull.

Gaga was the first word out of her mouth but unlike the other firsts in her life she had no memory of it. It was as if it had never happened. Sometimes she wished she could gaga again, especially when she felt that lump in her throat, fat as a hardboiled egg swallowed by a snake.

The grinding keeps us awake all night. The slipping noise of tooth against tooth, the squeak and rasp of shiny enamelled edges filing monotonously against an equal occluded opposite.

Dispatch by decapitation: A heavy-spined knife to sever her neck, slit open her belly, belly. Remove the guts quickly and set aside her head, fins swimming back to the sea; mouth gasping, gasping.

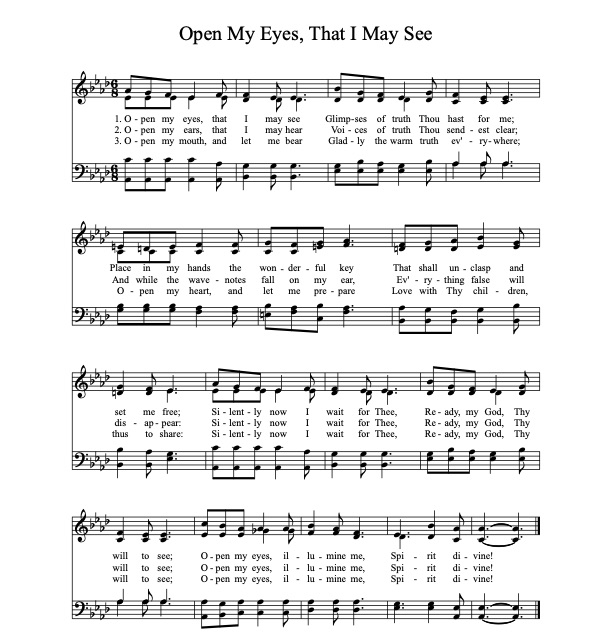

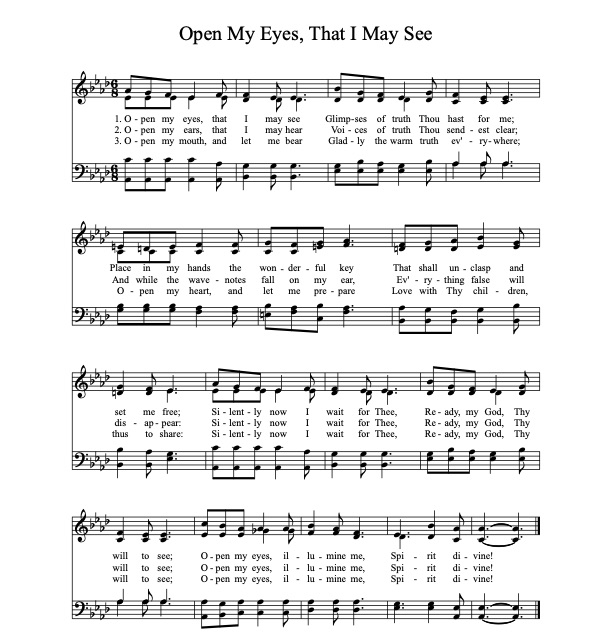

Clara H. Scott (1841-1897) was an American composer and in 1882 became the first woman to publish a volume of original hymns. She died in 1897 after being thrown from her carriage by a spooked horse. She wrote her most famous hymn, Open My Eyes, That I May See, in 1895, inspired by Psalm 119:18. Through my research in the archives of Rockingham Castle I discovered that this hymn opened each of the seances hosted by Florence Culme-Seymour throughout the 1930s. I reworked Clara’s original lyrics to give voice to the women whose presence can still be felt in the Castle today.

Dispatch by decapitation: A heavy-spined knife to sever her neck, slit open her belly, belly. Remove the guts quickly and set aside her head, fins swimming back to the sea; mouth gasping, gasping.

He is a red man all over, everyone can smell it. Even through the jasmine oil I apply so liberally before each shave he reeks of rusty iron and musk like the heavy gate to the bull’s field that was left open last year. I prattle on about the weather and tug my comb through his beard with my fingers crossed. Every time I snag on a knot I wince, afraid by the size of his huge hairy fists and the bulk of him sprawled across my biggest chair.

The dogs in south London are running. One of the big ones slows down as it passes me and I step back as its nose swerves into my crotch, waving my arms as though that would make any difference. If it were really hungry it would just eat me but I get a face full of hot meaty air and it’s a lucky day.

Teller 1: They are throwing stones again. The siren pulses through the streets, bouncing off the buildings almost as loudly as the glassy meteorites that cannot be cut or drilled by any material other than their own.

By Amy Lay-Pettifer: For I am Black Lie and I purr rumbling low. I growl hard when you touch me and when you retreat. I walk softly and I am to be followed.

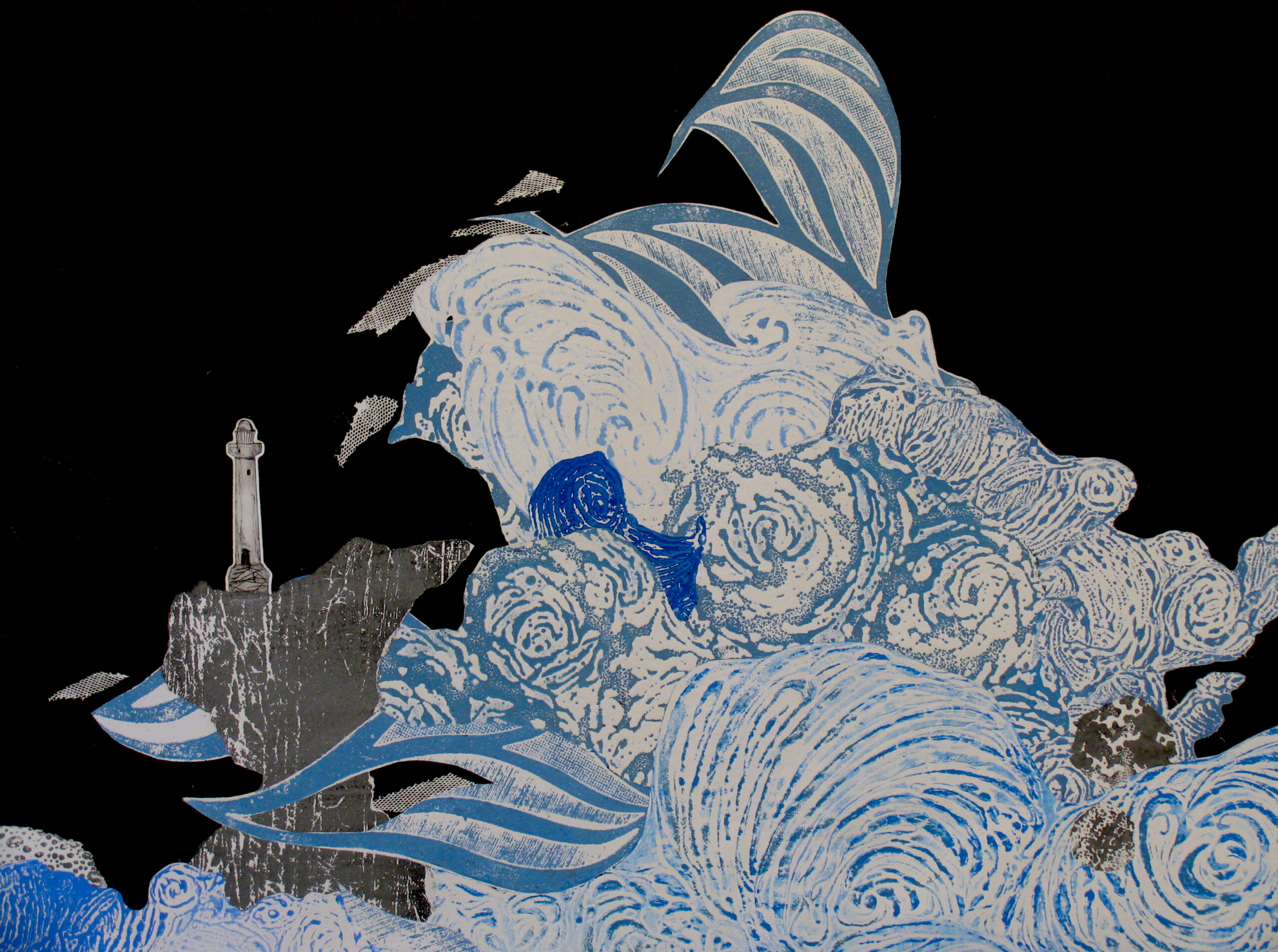

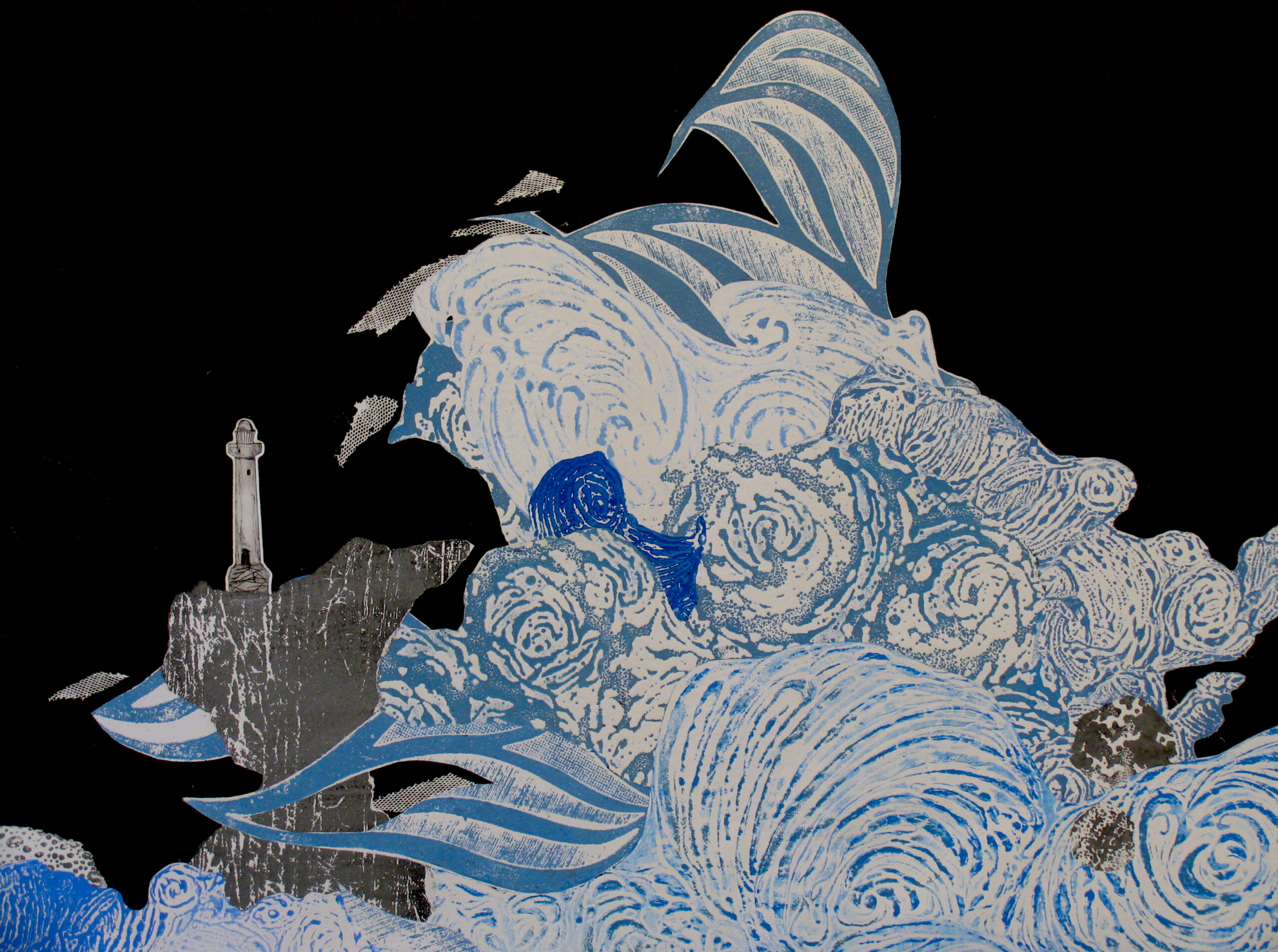

There was something wrong with the sea. The waves were oily and green and forest-filled, like the kelp had been ripped from its leathery footholds by a far away storm and carried here by the currents. A thick tangle of tentacles and skeins spread across the water holding bulging sacs that popped open as they reached the surface and spewed hundreds of bugs onto the undulating skin.

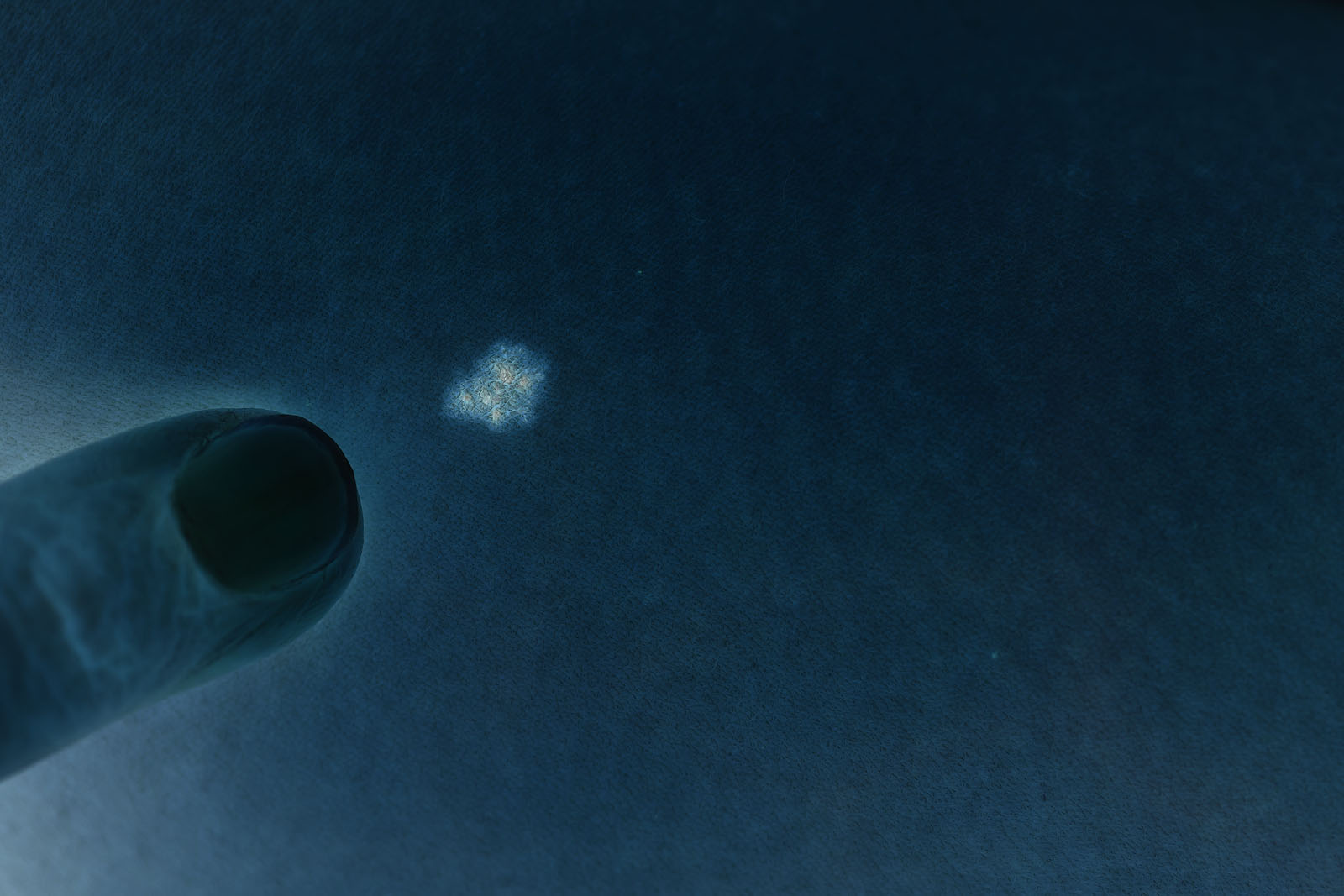

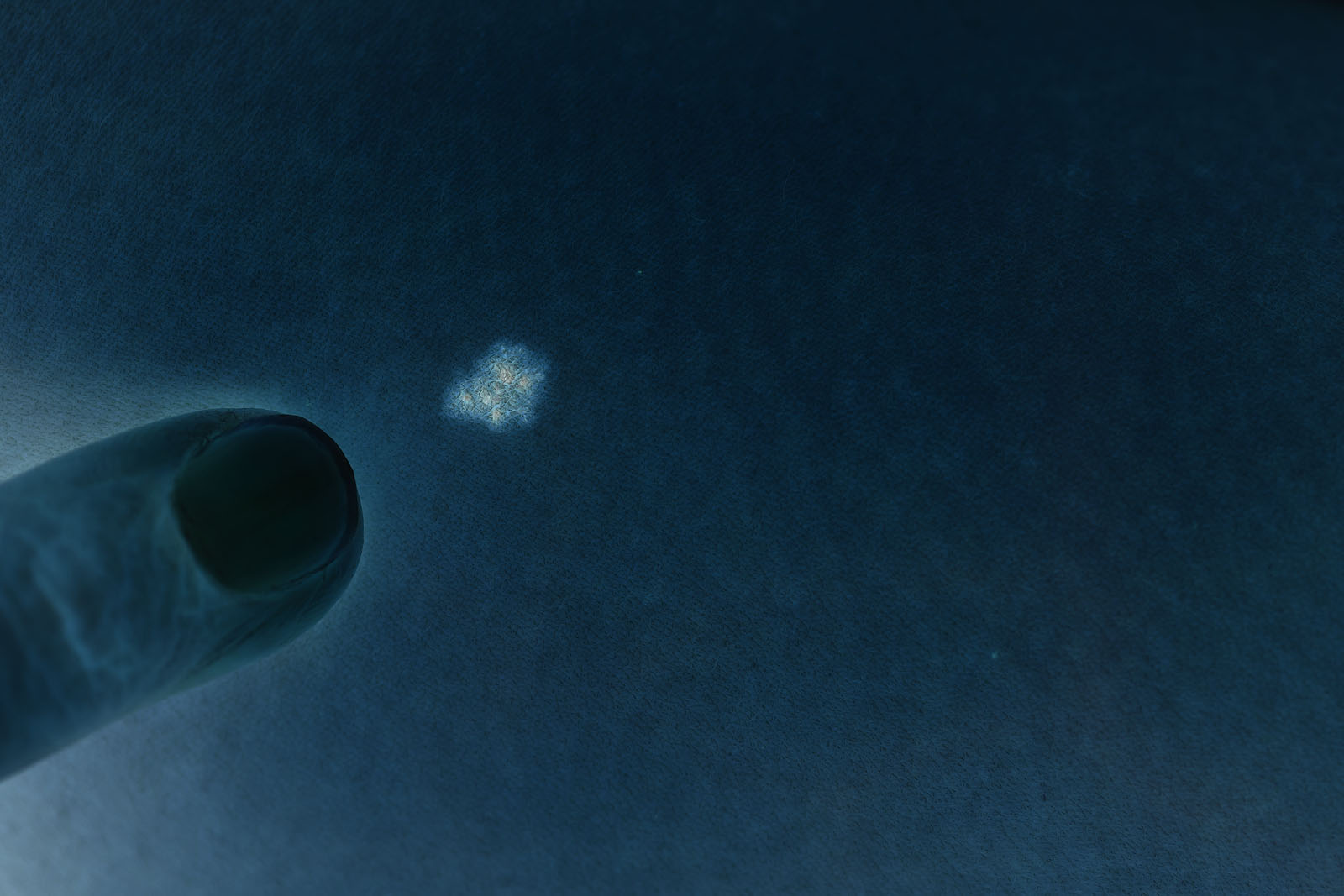

I lie in my bed, body warm and relaxed, waiting. When I open my eyes the glow-in-the-dark stars on my ceiling give me a little thrill. Outside low-lying cloud and light pollution hides the universe from me but inside this room I am watched over by Cassiopeia and Orion, the Plough and the Pole star and this makes me feel safe.

It is late when I see you moving into the flat above the pub opposite. Must be past 11, because I hear the doors swinging open, hot blue noise gulping for air.

They all saw her. Standing on the boardwalk outside the old woman’s house, smoking. The old woman was dying of cancer. Not from cigarettes, but still. They did not approve.

By Amy Lay-Pettifer: For Nin, poor Nin. For Nin neither. So much for you to hear and fear, that owl hoot and dog bark is not for you. Come out from under your wing soft down. You are needed.

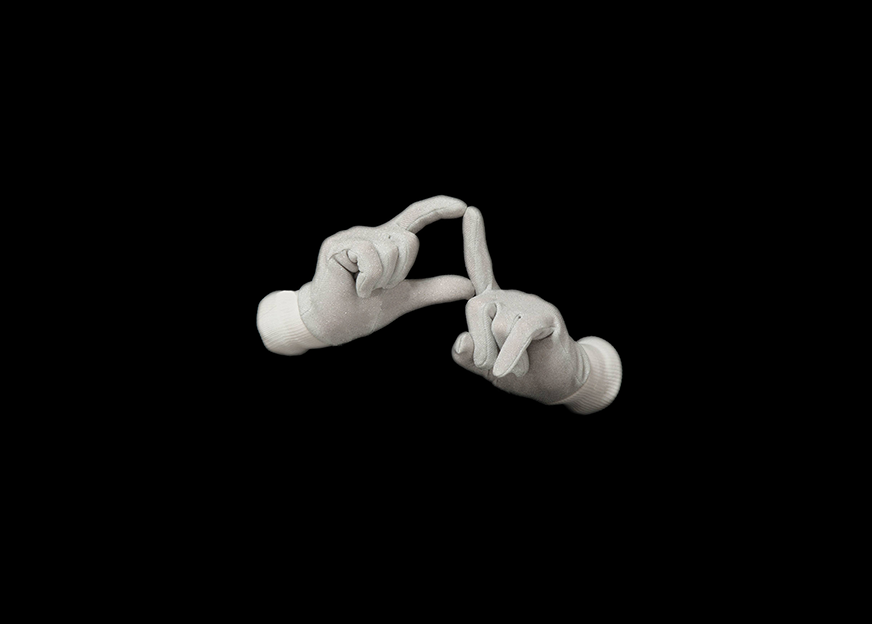

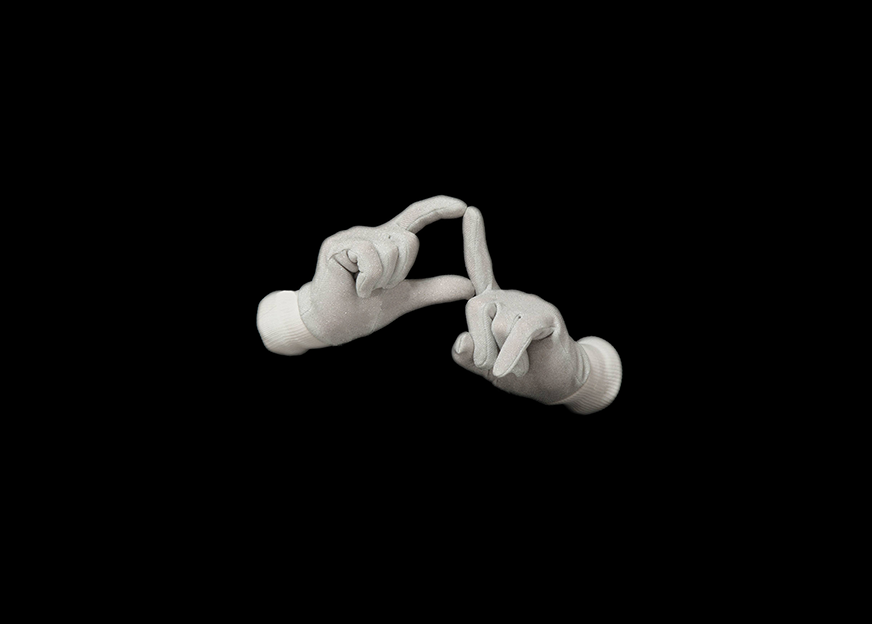

“And this is the sign for asleep,” says Alison, closing her index fingers and thumbs together in front of her eyes. “Go to sleep now my darling.” She smooths out the duvet cover with her hands, uncreasing the printed astronaut suit, flattening the stars in their cotton void, repositioning the blue Earth from sliding off the side of the bed. She kisses Bill’s hair, feeling his fragile skull millimetres away from her lips. “Night night.” “Night night Mummy,” he says.

Northland is the most enigmatic of isles; the fog descends early evening, roiling down the verdant mountainside and obliterating not only the vista but, it seems, the trees, lakes and I fancy, the soil itself, as in the morning, all appears different and new.

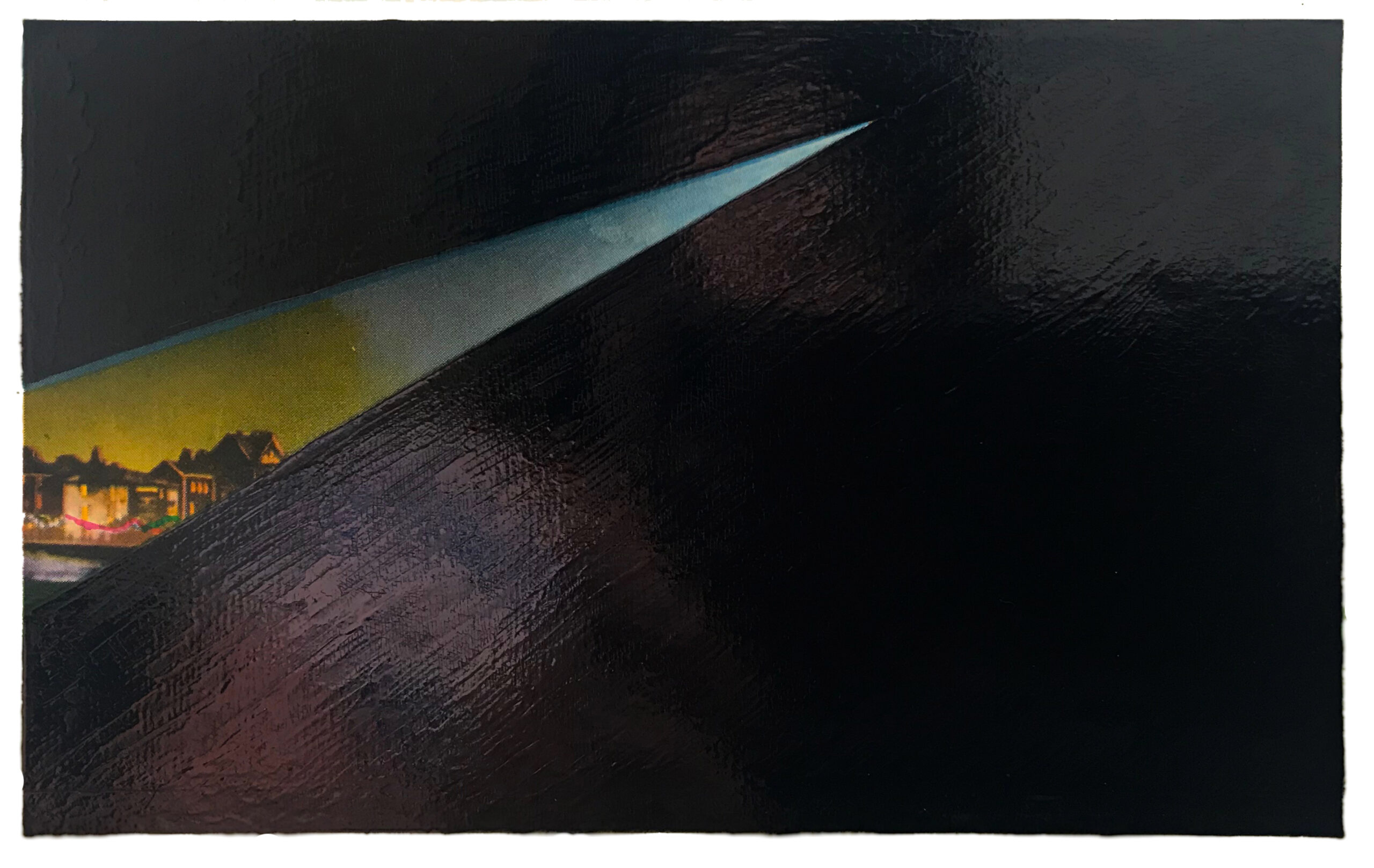

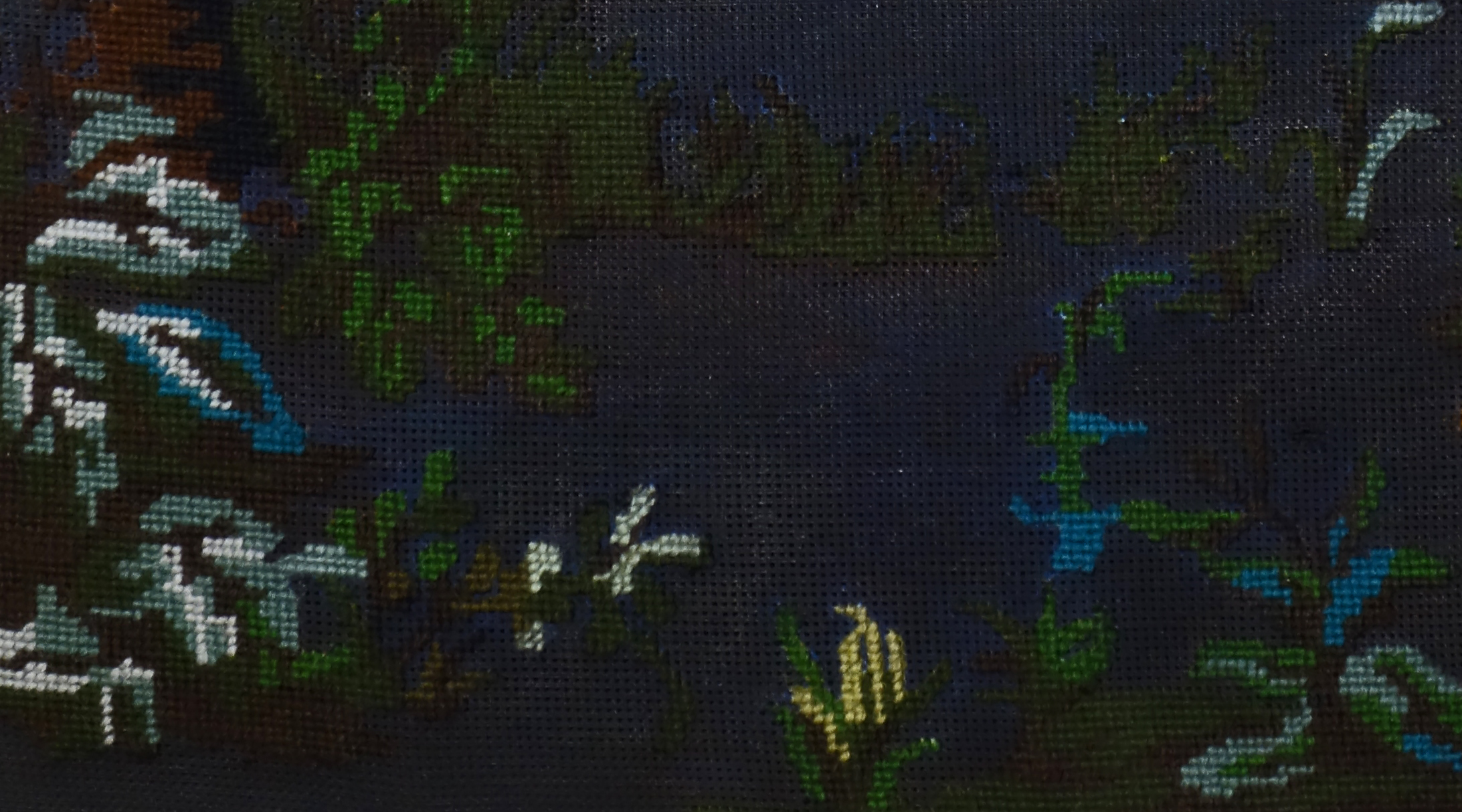

Sarah Gillett: We are looking out the window and seeing the world through glass, not able to physically touch it.

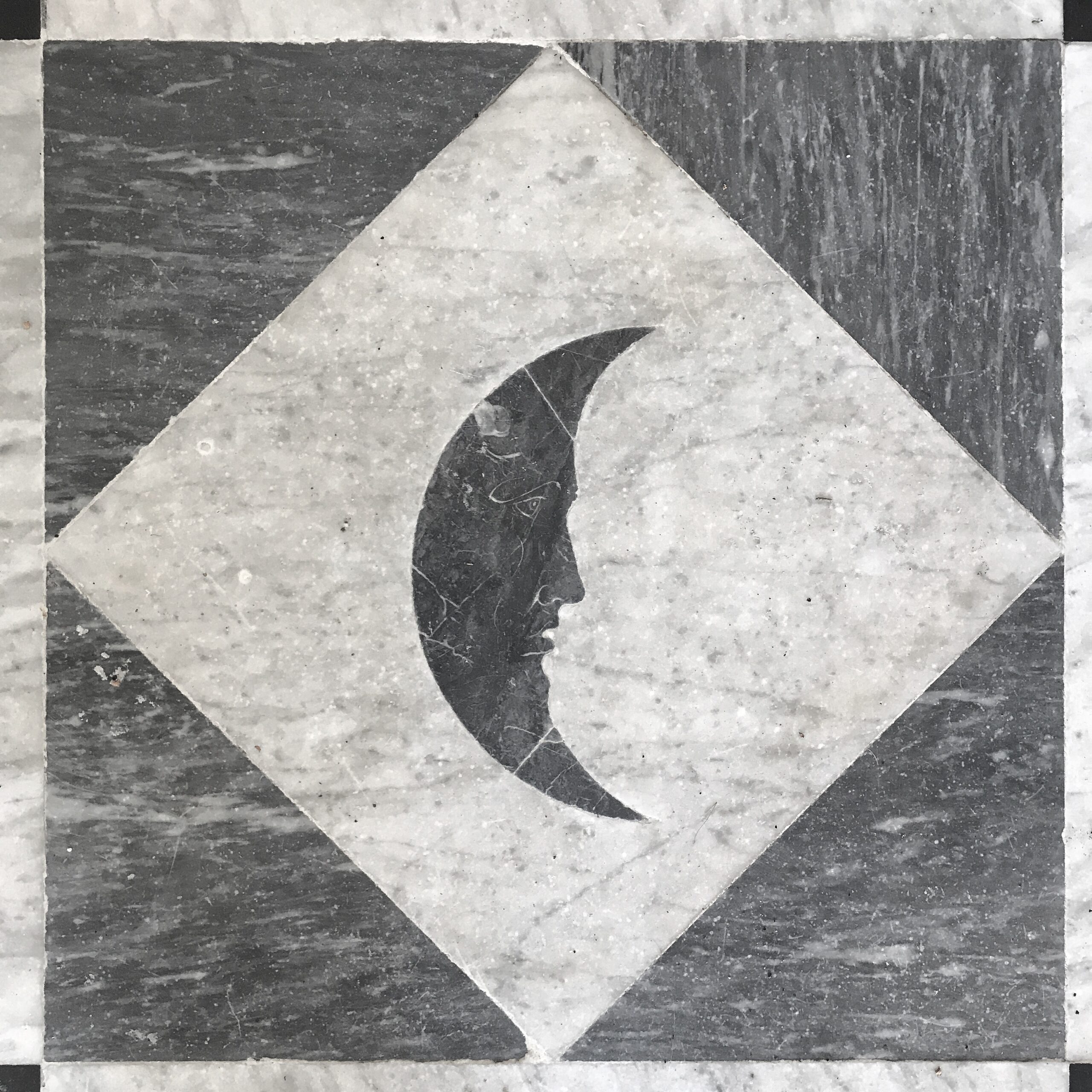

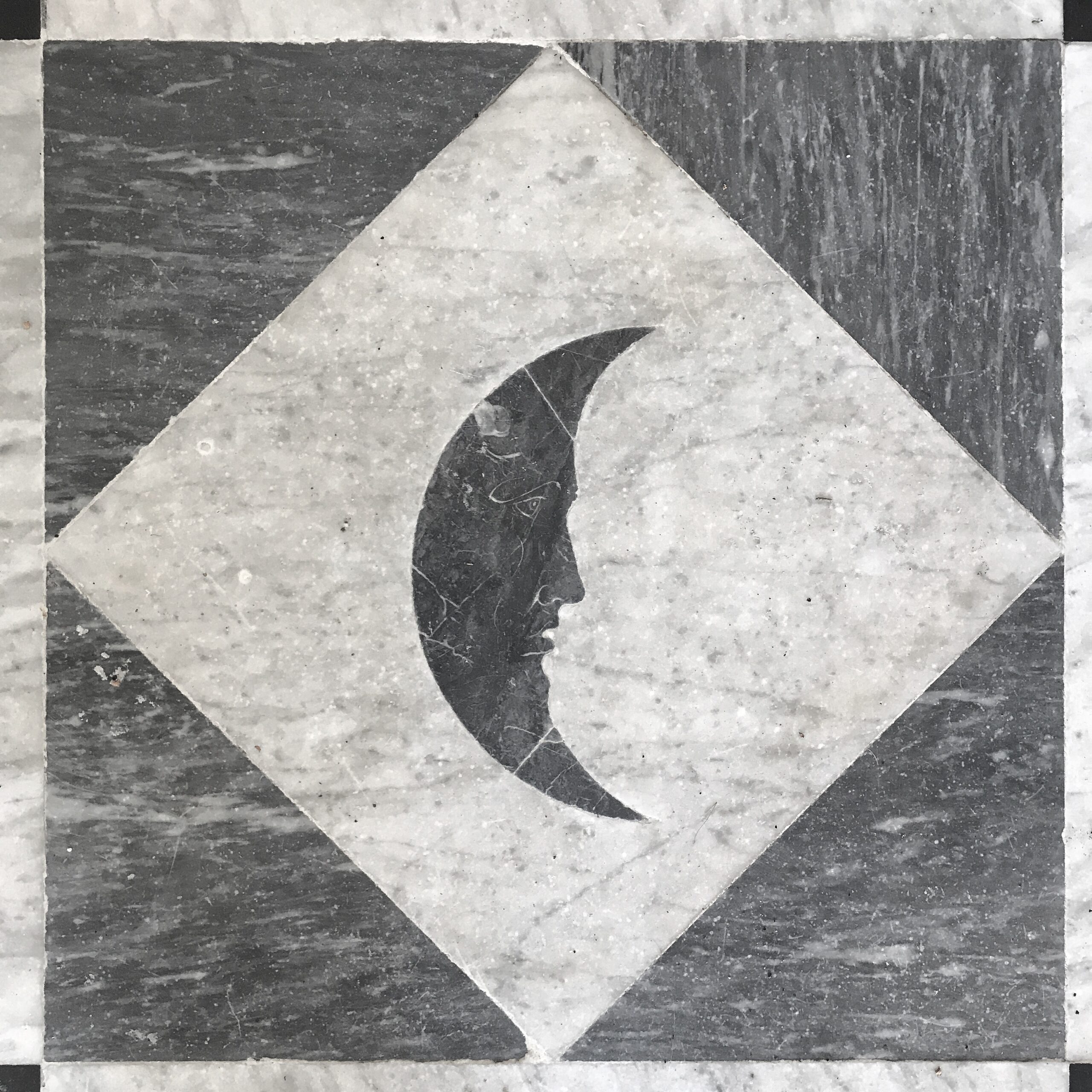

Welcome to the Fermynwoods Contemporary Art Podcast, hosted by Jessica Harby. This episode is a talk with the artist and writer Sarah Gillett as she begins a new body of work that explores landscapes of the nighttime.

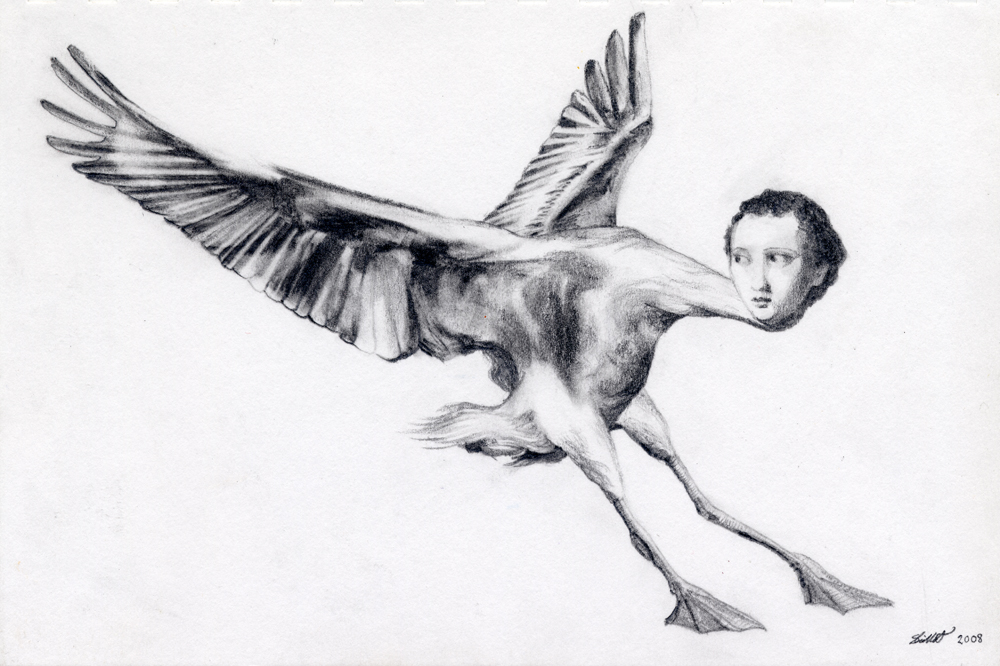

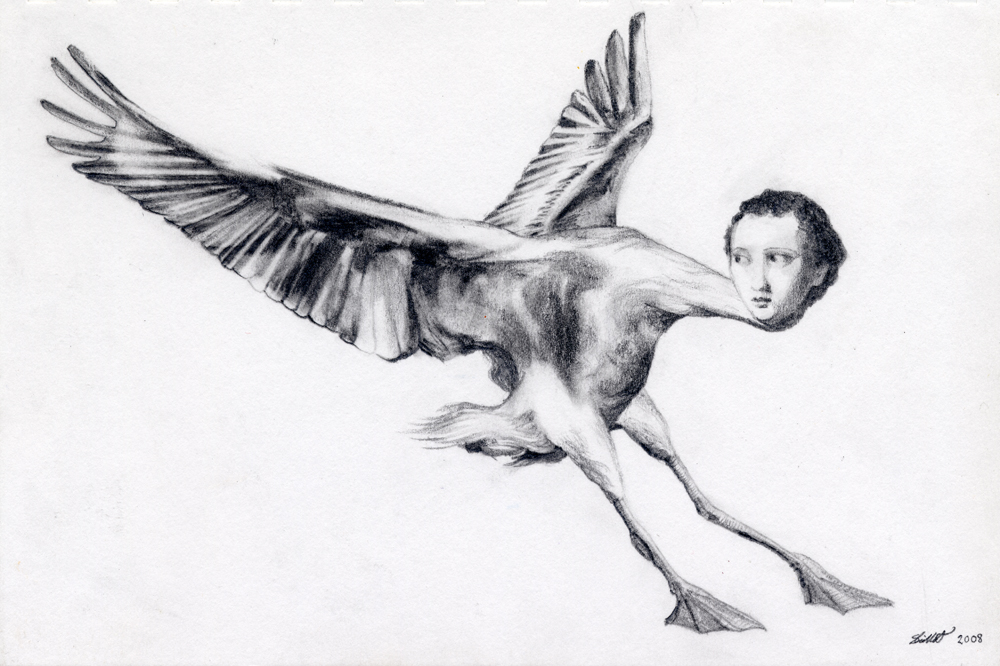

This conversation between Sarah Gillett and the writer Amy Lay-Pettifer digs deeper into the artist's relationship with Paolo Uccello’s painting The Hunt in the Forest (1470) and her wider art practice.

A collage audio piece recorded live on my phone at a gathering in a flat in Hackney. I handed out sections of a landscape poem that I had written to the group of women who had assembled and we sat on the floor in a circle.

Uganda is hot and dark. Late into the December night we sit on planks in the back of a stripped out land rover. We are driven faster than our bodies would like, the speed rattling my bones, teeth, brain, recording equipment.

Strawberries are the taste of summer. Bite into one and it’s a nostalgic pleasure trip. The lazy slog and echo of a village cricket match. The twang of rain and tennis racket. The arrowhead dart of swallows quick and fluttering as a power surge, scattering across the screen as missing pixels.

"Most people whose mental digestion of the marvellous is quite robust will refuse to believe this account, and yet there must be a few whose hair has been stirred and whose hearts have beat an unusual tattoo at the sound of a 'Something Inexplicable' in the watches of the night. Our conclusion is that there are such things as spirits, and in believing, we tremble..."

The first audio work I made, this chant references the moors where I grew up and the mythologies embedded in this landscape.

In the end, it was neither a flash nor a tunnel. The kiss had lived through many breaths and many stories, from the eager tongues of fairytale princes to the dry rubbery gums of the dying in hospital beds. Once there had even been a woman who changed into a pillar of salt.

Sarah Gillett is an artist and writer from Lancashire, UK.

She currently lives in London.